OUTSIDE LOOKING IN

Liverpudlian designer Steven Stokey-Daley deconstructs the English public school fantasy, and builds new communities along the way.

By JON ROTH

Photography WILLIAM WATERWORTH

There once was a boy who felt like an outsider. After some searching, he thought he’d found his place in the theater, but then changed his mind. He pursued fashion instead. As he studied, he became enamored of an entirely different culture, one worlds removed from his Liverpool upbringing. He looked to the touchstones of the English elite: their public schools, their universities, their strange rituals and costumes, and the books and films that enshrined them.

He was fascinated, though not quite admiring, of this other world, and he decided to reinvent it for his graduate fashion collection. He paid homage to the old costumes, but he picked them apart, too, making them feel fresh, subversive, exciting.

As soon as he presented his collection, the world shut itself up, fending off sickness. Back home, the boy – now a man – worked furiously. People had seen his clothes, and they wanted more, more, more. By the time things opened back up, and he could present his collections as intended, the fashion world took note, stood up, applauded, and invited the outsider in.

That is the fairy tale version of the Steven Stokey-Daley story. There is something about the 24-year-old British designer’s journey that evokes that mode: maybe it is his sudden, skyrocketing ascent from student designer to toast of London’s fashion crowd, or maybe it is the sense of romance and nostalgia he imbues in his own collections. But there is more to tell here than fits in a fable. Let’s start back at the beginning, as Stokey-Daley tells it.

As a boy, the designer grew up on ex-council housing outside the city of Liverpool. He describes himself as proudly working class, but admits he didn’t really resonate with the environment around him – specifically, the clothes. “The uniforms and the clothes of the people around me when I was growing up had cognitions of toxic masculinity and heteronormativity that we were all taught at school,” he says. “I never felt as if I belonged to any of that. I missed the lack of male glamour in the day-to-day uniforms of the people around me. It would be head-to-toe single-color sportswear and it would always be a black tracksuit and it never rang any bells for me.”

If there was a sartorial and cultural disconnect around him, Stokey-Daley found an escape, and an opportunity for creativity and play, in the theater. At 16 he became a member of Great Britain’s National Youth Theatre, an arts program that provides young people ages 14-25 with opportunities both onstage and backstage. Of the experience, Stokey-Daley has said, “It was the first time I met like-minded people, my lifeline to culture that opened up the possibilities of what I could do.”

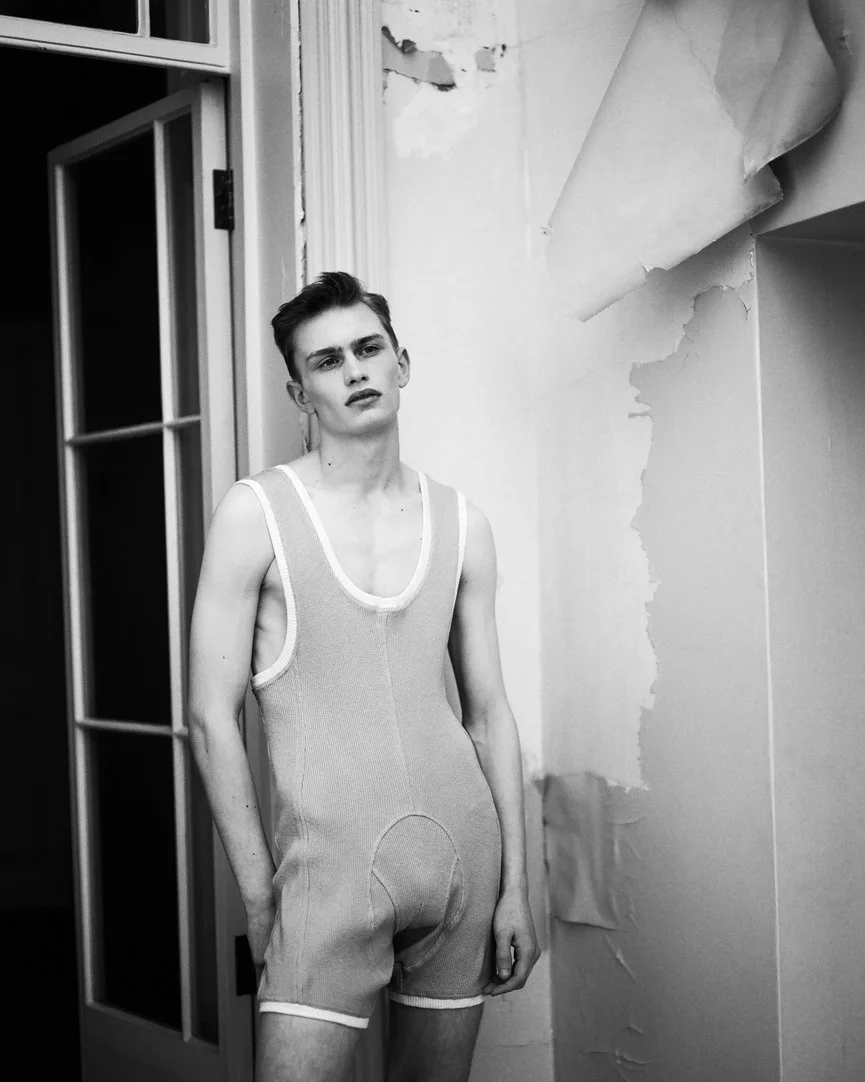

But theater would be a springboard, not an end point for Stokey-Daley. Two days before he was set to leave home for a graduate degree in English literature and theater, he changed his mind, applied instead for an art foundation, and found himself involved in design. This last-minute change of heart would eventually bring him to University of Westminster’s fashion program, where the designer began to focus on menswear. Immersing himself in this new world, Stokey-Daley uncovered an abiding interest in the English public school system, looking both outward – to the boys at Harrow School, processing to class in their straw boaters and blazers – as well as deep within the archives of the university. At one point, the designer has said, "I came across images of a regatta, and I had never seen anything like it before.” After growing up in the relatively rough-and-ready North, Stokey-Daley was fascinated by this alternate universe of pomp and circumstance, flowery dress, and strange customs. “There is something inherently feminine about that hyper-masculine culture,” he said.

From these twin views of the same, alien world – the present-day school boys and the antique photograph – the designer delved deep into an extremely rich vein. Through both archival sources and fictional accounts, there’s no shortage of references for a young designer looking to unpack the subtleties and strangeness of elite, English academe. It’s a world steeped in money and power, masculine aggression, subjugation, strict class divisions, and the bizarre customs that tend to spring up in such rigidly artificial environments. Stokey-Daley often makes references to novels and films like “Brideshead Revisited”, “Maurice”, and “Another Country”, the work of famed photographer and all-around aesthete Cecil Beaton, and the British Royal Family – often as seen through the lens of Netflix’s “The Crown” – to name a few.

This canon of references has some influence over much of the English-speaking world – a vestige of Great Britain’s past imperial power. But what about it appeals so much to Stokey-Daley, an Englishman himself? “It’s super interesting to look at it from the outside. That’s why there’s so much obsession internationally with British traditionalism,” he says. “For me, I felt a little bit like an outsider when I looked into it also, because I never had access to any of that when I grew up. It wasn’t something that we came by where I’m from. I almost felt like I had to have that outsider obsession that the world seems to have with Britishness. I’m not too sure what makes me so obsessed to be honest. I think it’s a world of complete frivolity and femininity that generally is an end product of hyper masculine and heteronormative.”

The designer’s Liverpudlian, working-class remove keeps him so fascinated by this other world – one that exists on the same island, but feels light-years away. No one could deconstruct these upper-class conventions in quite the way Stokey-Daley has, because his own sense of self is both at odds with, and adjacent to, his subject.

There is also an aspect of social commentary to his work, as Stokey-Daley is quick to point out. “I’m unpicking the lines that guard the barriers between classes and an observation of these two aesthetically different worlds,” he says. “It’s all about access to higher education and culture and the disparity between the classes and the access.”

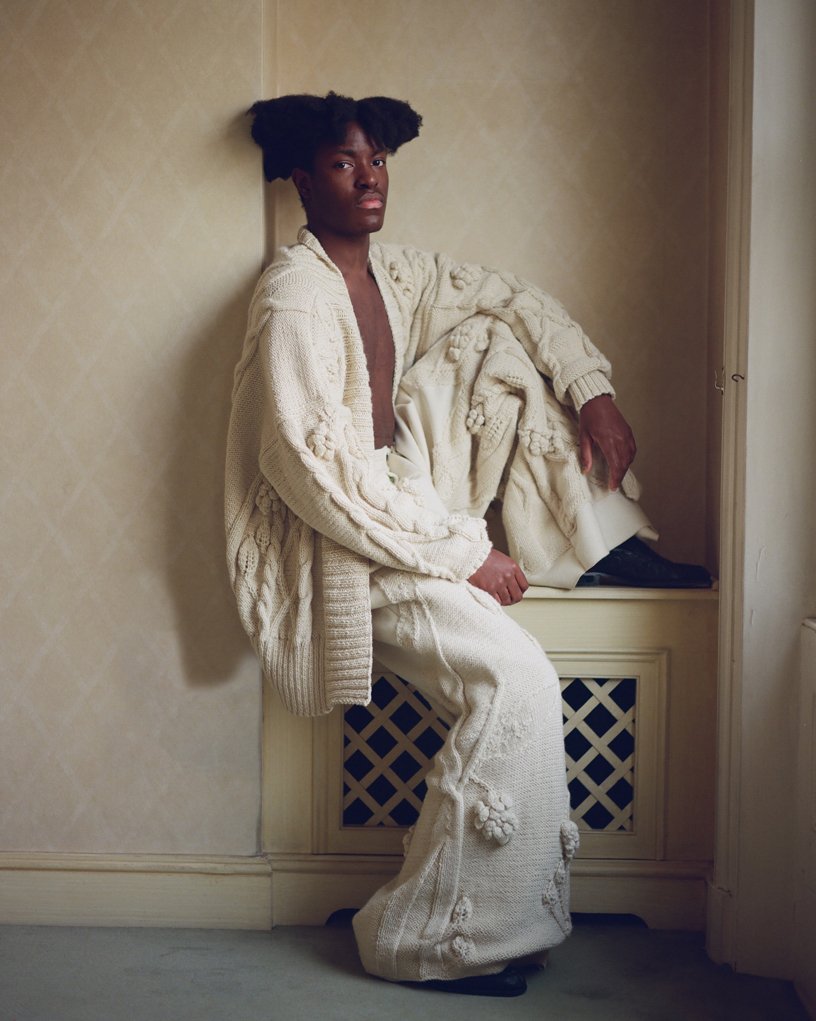

All heady and important stuff, but how does it come to life in an S.S. Daley collection? Picture an antique photo album from Eton or Harrow, as seen through the looking glass, or a snapshot of those same students in fancy dress, staging an impromptu tableau. All the fundamentals of the public school wardrobe are there – the wide, pleated pants, the bedecked boater hats, the union suits and knits and dressing gowns – but they take on an exaggerated, romantic quality under Stokey-Daley’s artful hand. The pants, for instance, have ballooned to a volume that feels avant-garde, not old-school. Shirtsleeves flounce out in extravagant bell shapes, and hats are festooned so elaborately they take on a Bacchic abundance. Everywhere there are snippets of tapestry, ribbons, and embroidered tablecloths given new life. These are not carbon copies of old clothes, but fantasies on that theme. S.S. Daley pieces shake up these seemingly stolid garments of another era, presenting us with daring new interpretations.

We look to the next generation to interrogate the status quo, and Stokey-Daley doesn’t stop asking questions once he’s completed a collection. He holds strong opinions on the pace of the current fashion cycle, which he thinks ought to break away from a seasonal calendar, and on sustainability, too – a topic heavy-hitting corporations tackle with uneven results, but a smaller house like Stokey-Daley’s can work into its philosophy more naturally. “I think we see a lot more people and bigger companies using sustainability as a ‘green washing’ sort of thing, which is why I’m careful when I speak about sustainability,” the designer says. “I make a very conscious effort to do my best.” While he caveats that fashion can’t ever be 100% sustainable, he doesn’t use any synthetic fibers and ensures upwards of a third of his collections are made up of upcycled, one-of-a-kind pieces. Sourcing these reusable materials is one of the designer’s favorite activities: hitting up Portobello Road and other markets across the country, north and south, finding fabrics that were once drapes in a manor house, or slip-covers for cruise ship chairs. “We then have the whole process of making the most of the material and cutting them into garments, and finishing them in a way that is respectful to how the original piece was made,” he says.

S.S. Daley pieces have been in demand almost since his graduation from his university – thanks to his creative-but-wearable designs, some crucial endorsements from bold-faced names, and possibly our pandemic penchant for romantic statement pieces even if we’re just wearing them from home. In 2021, MatchesFashion brought S. S. Daley into their Innovators program, which offers mentorship and content support to up-and-coming designers, in addition to stocking their pieces on the site. The program also provided an opportunity for Stokey-Daley to sit down for a conversation with one of his fashion heroes, Thom Browne – a designer who has cornered Americana in much the same way Stokey-Daley is owning and upending a certain sartorial Britishness.

All this success has meant Stokey-Daley has had to ramp up his production in an incredibly short amount of time. He’s gone from sewing at university and in his childhood home to enlisting a small team to help produce his garments, most of them within his hometown, many of them friends of his grandmother, who used to work in a clothing factory but now helps out in a more managerial capacity. “We’re sort of forming a small localized production setup that brings them back to do what they love to do,” the designer has said of his team. He’s taken pains to encourage local industry when it comes to fabrication, too, citing custom-woven silk he sources from a family that’s been based in the United Kingdom since 1805. “It’s about sustaining traditional heritage modes of the industry,” he says.

As he continues to build out the S.S. Daley universe, Steven Stokey-Daley seems excited about the idea of community in its many forms. He is creating an immersive world for his customers, of course, but he is finding new connections all along the way: bridging theater and fashion with his runway presentations, and enlisting aid from hometown experts as demand for his garments grows. The designer may draw inspiration from his outsider’s view of the tightly guarded, exclusive world of the English upper class, but he’s proving again and again that sometimes the most fruitful work happens when we shake off old partitions and work together to build our vision instead.