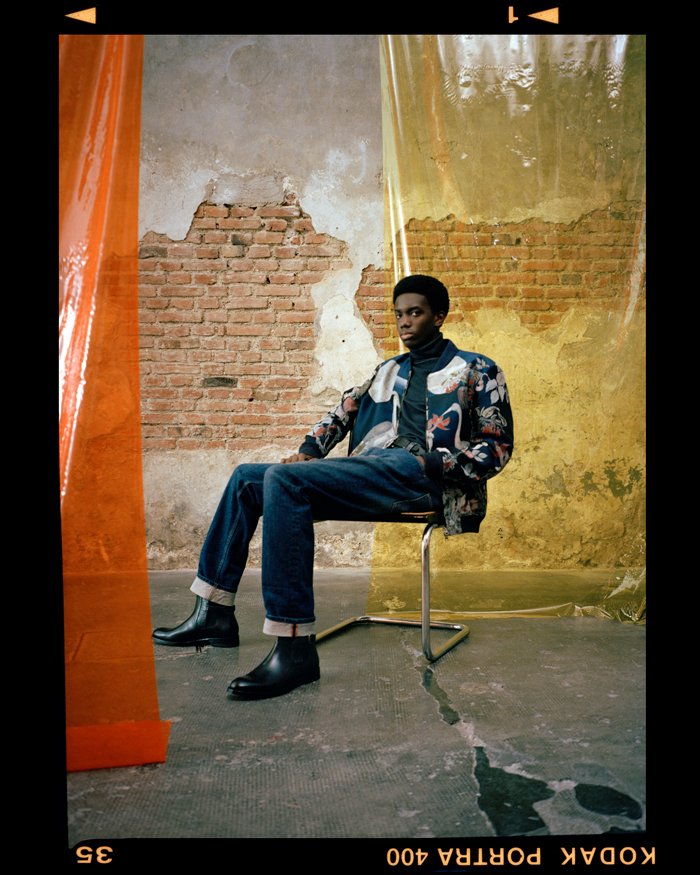

A HEAD FULL OF DREAMS

Photography MARCO IMPERATORE

Styling EMIL REBEK

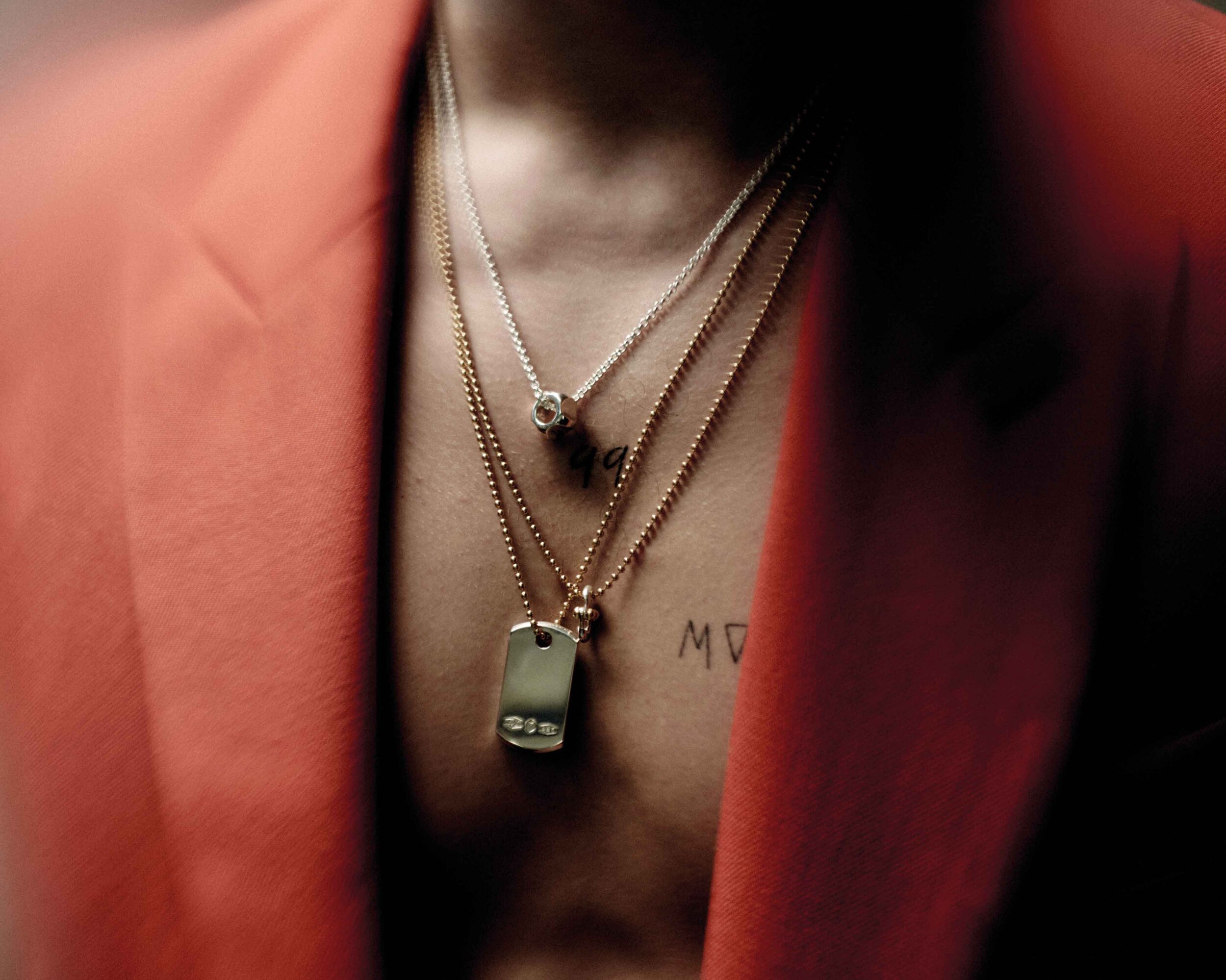

NOW YOU SEE ME

Photography MARCO IMPERATORE

Styling EMIL REBEK

TIME AFTER TIME

Photography MARCO IMPERATORE

Styling EMIL REBEK

PORTRAITS OF A MUSE

Photography MARCO IMPERATORE

Styling EMIL REBEK

HOW BEAUTIFUL WE WERE

Photography LAURA MARIE CIEPLIK

Art Direction KADURI ELYASHAR

Fashion DIOR

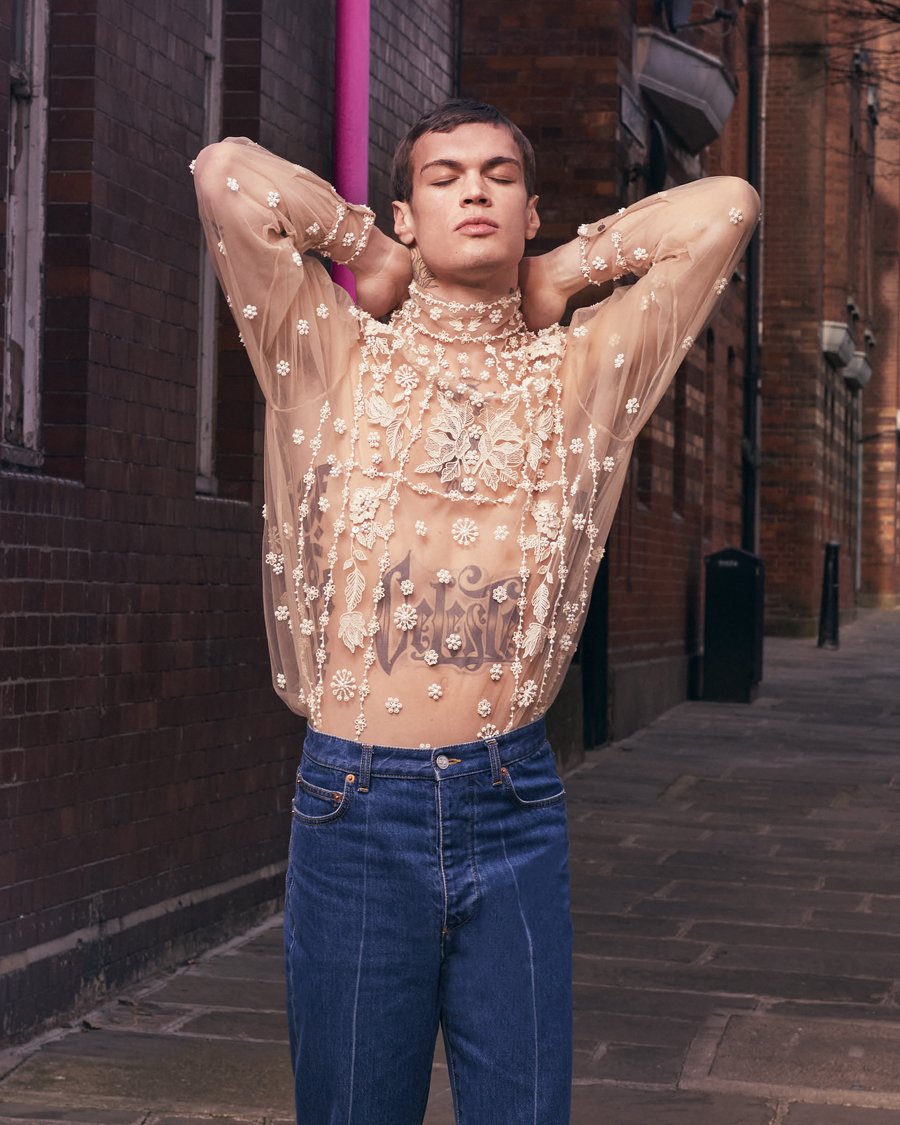

LEAVE THE WORLD BEHIND

Photography FILIP KOLUDROVIC

Styling GIOVANNI BEDA

Model YULIAN ANTUKH

Casting REMI FELIPE

Grooming FEDERICA CANCIAN

Executive Producer JUSTIN GERBINO

Producer MIKE GERBINO

Production PBJ

HOMESICK FOR ANOTHER WORLD

Photography LAURA MARIE CIEPLIK

Art Direction KADURI ELYASHAR

Grooming JÉSSICA CARVALHO

Casting REMI FELIPE

ON THE ROAD

Photography JAIME CABRERA

Styling BEN PERRIERA

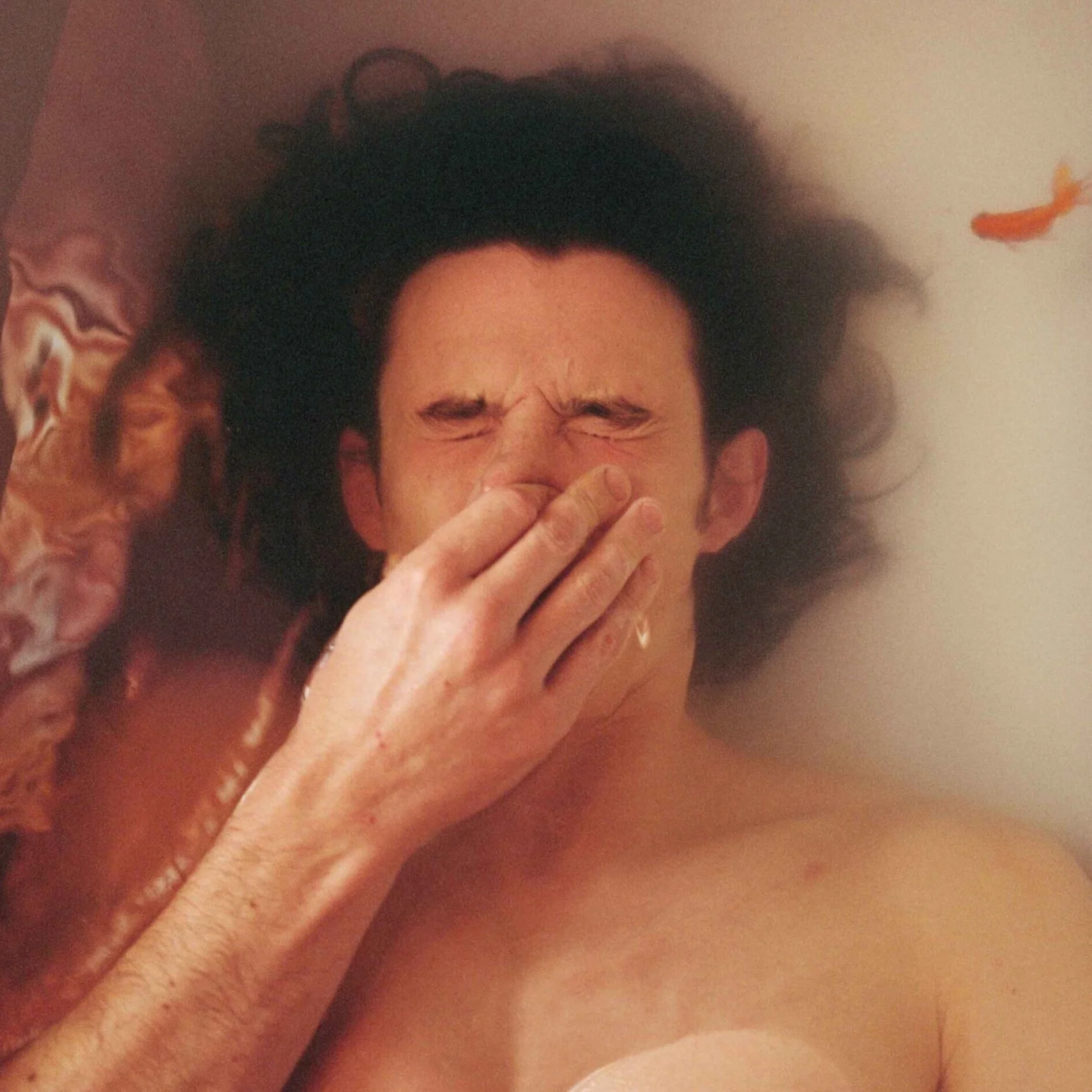

BOYS DON'T CRY

Photography PABLO SÁEZ

Styling GABRIELLA NORBERG

Grooming ANDRE CUETO

Set Design AYMERIC ARNOULD

FUTURE NOSTALGIA

Anthony Vaccarello’s tribute to the late Yves Saint Laurent's enduring love affair with Marrakech comes full circle with a powerful statement of the future that lies ahead for the venerable French fashion house.

By HASSAN AL-SALEH

The circle is a universal symbol with inextricable meaning. It has no beginning and no end. It represents evolution as a process of transformation. It symbolizes, eternity, infinity, unity, totality, timelessness, the self. It is omnipresent.

In many ways, Anthony Vaccarello’s presentation of the men’s Spring-Summer 2023 collection for the illustrious house of Saint Laurent came full circle. It was held for the first time in the majestic and ancient desert city of Marrakech, a place of particular resonance for the late Yves Saint Laurent - a spiritual escape where he found inspiration and solitude. The collection was a beautiful, moving and mesmerising exploration of fashion where the lines of masculinity and femininity elegantly dissolved - firmly set in the future but harking back to a bygone era of timeless elegance entirely devoid of clichés.

The show was visceral and profound with the juxtaposition of the dramatic rocky landscape of the Agafay desert and the futuristic set designed in collaboration with London-based artist and designer Es Devlin, which included a vast illuminating disk emerging from a pool of water in a makeshift oasis as a metaphor for life’s fascinating complexity. Otherworldly by any measure.

In the words of American writer and composer Paul Bowles in his novel of alienation and existential despair, The Sheltering Sky, “We think of life as an inexhaustible well. Yet everything happens a certain number of times, and a very small number, really. How many more times will you remember a certain afternoon of your childhood, some afternoon that's so deeply a part of your being that you can't even conceive of your life without it? Perhaps four or five times more. Perhaps not even. How many more times will you watch the full moon rise? Perhaps twenty. And yet it all seems limitless.”

Limitless. Limitless bounds of possibility was precisely what Vaccarello displayed. A powerful statement of the future that lies ahead, in rhythmic and cyclical movement.

NEVER PARTED

Hoor Al Qasimi is pushing boundaries with renewed vigor and purpose as the physical and philosophical heir to the Qasimi brand.

By LAURA BOLT

Photography MOUS LAMRABAT

It’s been said that talent runs in the family, and the Al Qasmi twins are certainly evidence that that may just be true. Born to Emirati royalty, both Khalid Al Qasimi and his twin sister Hoor were and are creative forces in their own way. Hoor made her name as a powerhouse in the art world, shaping the artistic legacy of Sharjah. The Central Saint Martins educated Khalid, meanwhile, had been making waves in the fashion industry for over a decade with his eponymous line Qasimi, which explored concepts like identity, politics, and culture through sharply designed clothing and his romantically hopeful vision of the Middle East’s future.

Khalid’s label was a proud representation of his country and heritage, as well a platform for the designer to explore issues of home, representation, and poetry. “Qasimi is a way for me to discuss what's going on around us, whether it is politics or economics,” he once said, later adding that “there are always different ways of viewing things. With my background, politics is very much embedded within our situation in the Middle East. We are always discussing politics, at home, over dinner, it’s present in conversation all the time. That’s something that I don’t necessarily see in fashion: politics within the clothes, translating politics and history into fashion.”

Unfortunately, a dream realized became a dream deferred when Khalid Al Qasimi died unexpectedly in 2019 at the age of 39. Still in mourning, Hoor Al Qasimi vowed to keep her brother’s vision alive by seeing to it that his work at Qasimi hasn’t been in vain. With the caveat that, “It will always be my brother’s office, my brother’s team, and my brother’s label,” Hoor took the reins of Qasimi as Creative Director and is now honoring her brother’s legacy while building a future for the brand that is distinctly her own.

“His aura is still present at our London studio, with his original sketches lying around. It’s a strange feeling knowing that your twin is longer with you,” says Al Qasimi. “So, occasionally, I’ll scroll back to our log of phone messages and revisit references that he was heavily inspired by.” She relied heavily on the existing team while infusing the work with her own sensibilities. The challenge was to create a living memorial and honoring clothing, techniques, and certainly people from the past, while firmly stepping into the future.

When she began to work on the label, Al Qasimi admitted that the steep learning curve was easier to navigate due to her connection to her late brother, saying that, “Fashion is new to me. So, one of the biggest challenges will be to learn and absorb as much about the industry as I possibly can. Luckily, Khalid and I always played as a sounding board for each other in our separate endeavors, him for me with art, and myself for him in fashion – so I feel well connected to it.”

As she explored a new realm of creative potential, Al Qasimi expanded not just her mind, but also the brand, introducing a new womenswear collection to the label. For Hoor, “Rather than a couple, the Qasimi woman is very much a soulmate to the Qasimi man. They are two parts of one story.” It was a move that felt poetic, representing the new feminine energy that flowed through the house, proof that the end of a life can still open the door to expansion and the power of memory doesn’t have to fade.

Under Hoor’s tutelage, the brand found its stride by taking inspiration from the past to build it’s future. “The brand wanted to look back at its cultural heritage, more specifically textiles from the Arabian Peninsula”, she said of her debut. “We used it as patchwork in the jersey collection and on accessories, as well as entire pieces of outerwear, trousers and headwear. Like the weavers, at Qasimi we also interpret the world around us to try to make sense of things, imparting our own creative input into the garments we design.”

While she’s undertaken the new endeavor with courage and vigor, Hoor has remained faithful to her background in the art world, using her knowledge as inspiration for her work. A constant champion for underrepresented groups and political activism, Hoor has built a career advocating for and highlighting artists that speak truth to power and aren’t afraid to ask tough questions. Judging by her work so far, it’s a passion she intends to bring to her role at Qasimi.

In fact, it was her experience directing the Sharjah Biennial which led to a collaboration with American artist Nari Ward, for which Ward created a rap dubbed We The People that evoked themes of racism and youth culture. “The overarching concept of the collection is about diversity and change through unity, civil responsibility and equality,” she said of the inspiration for the collaboration. “So once the protests against anti-black racism began, the collection started to take on a new, more profound meaning, reinforcing the brand’s mission to address political and social issues.”

Addressing social issues has always been central to the DNA of the Qasimi brand. In a past “False Flags” collection, Khalid experimented with ideas about immigration, militarism, and globalization, imbuing his clothes with a deeper message than simply looking smart. Speaking of his boundary-pushing designs, Khalid once remarked “It’s very easy to self-reference in my opinion, and whilst I touched on Middle Eastern style… it really wasn’t so much about my background as it was about ideas of movement. The idea of mixing two opposing ideas together goes a bit deeper than myself. There was this idea of pacifying military clothing, minimalizing it. At the risk of a touchy subject, there were ideas of terrorism as well. This is more about the state that we’re in and the symbolism of certain things. To a Western person, some aspects of traditional Middle Eastern clothing are perhaps seen as aggressive or threatening, but if you look at it from the other point of view, the traditional Western military outfit could be much more threatening, or indeed terrorizing. It’s about how you view things and the ways we create meaning.”

Ultimately, creating meaning remains the throughline of Qasimi, no matter which Al Qasimi twin’s hand is driving that meaning. Aligned in their mutual curiosity, artistic and worldly upbringing, and confidence to stand up for what they believe in, it’s become clear that Hoor is truly both the physical and philosophical heir to the Creative Director throne.

The East-meets-West dichotomy is another brand fixture that Hoor intends to continue to explore, noting that “the brand’s connection with both the West and East epitomizes Khalid’s (and my own) identity. We grew up between the two worlds and so London was home to my brother and therefore a big part of Qasimi’s identity.” It's a logical step for a woman who once said about a biennale, “Why country representation? Nobody’s from one country!” It seems that for both Al Qasimi twins, at the end of the day, pushing boundaries is just another way of making connections.

Only time will tell what Hoor will dream up at Qasimi, though it's a safe bet that weaving traditional Middle Eastern fabrications and styling with a global slant will always be part of the brand. Just as she had to let go of her brother, it’s clear that Hoor has a uniquely deep understanding of the ideas of permanence and legacy. “I don't like the word permanent very much,'' she has said. “For example, with monuments that you walk past every day – at some point you end up not noticing them anymore. They just become a normal part of the landscape. So if you're trying to engage with your audience, it is more interesting to have thought-provoking interventions.”

It is a heavy task, stewarding the vision of someone you have loved and lost, while also steering towards continued relevance in the ever-changing world of fashion. “I don’t feel like he’s gone sometimes, and I often dream of Khalid,” Hoor has said. Now that his dream is one they both share, it’s only fitting that he continues to have a place in hers. Qasimi will no doubt continue to be a compelling presence with a rich and complicated past, present, and future, but if there is one thing that will remain true, it’s that where love is concerned, some dreams will never die.

STILL HERE

Virgil Abloh dared to dream big and succeeded in remaking the luxury fashion landscape in the process. A tribute a creative force of his generation, and the next.

By JON ROTH

Let’s begin at the end.

On November 30, 2021, a fleet of drones spelled these words out in the sky above Miami:

VIRGIL WAS HERE.

The same phrase would soon appear on Louis Vuitton storefronts across the globe.

Two days earlier, Virgil Abloh, artistic director of menswear at Louis Vuitton, founder and CEO of Off-White, architect, furniture designer, DJ, a compulsive collaborator and tireless advocate for bringing in talent from the margins, died in Chicago, Illinois of a rare form of heart cancer. Abloh had kept his illness quiet after his diagnosis in 2019, and so the news came as a shock not just to the fashion world, but the world in general – Abloh was more than a fashion designer, he was a force that transcended disciplines. His sudden death at 41 cut short a profoundly creative trajectory, and could have been the end of a cultural moment.

If you are holding this magazine, you almost certainly know all this already. The ripples of Abloh’s influence are wide and deep, and even those unfamiliar with his name learned it in 2018, when his appointment as Louis Vuitton’s men’s artistic director made headlines across the world – “the first African-American man to head a French luxury house.”

Still, it helps to revisit the context, to list out Abloh’s accomplishments, to isolate what we know about his life and career. It is impossible to read the arc of a person’s life as it happens – especially someone like Virgil Abloh, whose boundless energy seemed to spin into countless new partnerships and projects every day. But when that person passes and the dust begins to settle, the major plot points start to become clearer. Themes stand out more starkly, certain words and phrases start to echo. It becomes easier to find the thesis.

Talk to any one of Abloh’s many, many fans and they will have their own take on his mission. One through line in his work and his words is that he was a man enamored of possibility. Someone who saw potential where other people would never look, and took pleasure in asking questions.

What if we lifted up kids from the margins and gave them the tools they needed to make change at the center?

What if we remixed and remade it all, collaborating, cross-pollinating, appropriating and improving everything all with gleeful, kid-in-a-candy-shop abandon?

What if we were kids again? What if we maintained that wide-eyed optimism and curiosity.

This last question also brings up a corollary to Abloh’s preoccupation with possibility: wonder. Possibility is a concept. Wonder is the feeling it elicits. Again and again, he returns to this feeling:

“I’ve been on this focus of getting adults to behave like children again. That they go back into this sense of wonderment. They stop using their mind and they start using their imagination.”

“I start from the wonderment of boys. When you’re a boy there’s one thing that adults ask you: What do you want to be when you grow up? And you say artist, lawyer, doctor, football player, fighter pilot. But then, if I ask what does a doctor look like? There’s a knee-jerk. That’s where we can learn.”

“I’m going to… continue this feeling of the whole freedom of being a child, still learning. I’m changing my pace drastically.”

Why shouldn’t Abloh come from this place of possibility and wonder? After all, his story proves that dreams can, in fact, come true.

The designer himself has acknowledged in interviews that his trajectory is unbelievable. “To come from designing a graphic t-shirt in 2012 to making it to a house to design a collection... As a young black kid from Rockford, Illinois, from immigrant parents from Ghana, West Africa, that was like, impossible, you know?”

He did it anyway.

A little background to ground ourselves in where Abloh came from, and where he was going: He was born outside Chicago. His father Nee managed a painting company and his mother Eunice was a seamstress (she taught Abloh how to sew). He got a Bachelor’s degree in civil engineering. An art history class in senior year inspired him to pursue a Masters in architecture in 2003. He was fascinated by architecture, particularly the work of Rem Koolhaas, and the idea that architecture isn’t just about buildings, it’s about systems. During this time, he wrote about fashion for website The Brilliance, and he designed clothes, too. Through connections at a Chicago screen printing shop, he entered the orbit of rapper/entrepreneur/provocateur Kanye West, and Abloh’s life entered a kind of hyperspeed.

Working with West, Abloh joined a small brain trust of the musician’s collaborators. He became a kind of walking encyclopedia of design history, always rooted in his eclectic affection for artists like Caravaggio and Mies van der Rohe, Koolhaas and the Bauhaus. “Kanye wasn't going to put his art form in the hands of the art department at the record label. So he was like, ‘I am going to hire you, and let's literally work on this 24–7, laptop in hand, nonstop,’” Abloh has said. “So more than any title, I was just his assistant creatively. I believed that this was going to be another chapter in hip-hop.”

As West’s interest in fashion grew, so did Abloh’s, and the two attended Paris Fashion Week in 2009 with a group of collaborators including Don C and Fonzworth Bentley. It was an eye-opening moment for Abloh, who saw an opportunity in what felt like an airless fashion scene. “When Kanye and I were first going to fashion shows, there was no one outside the shows,” Abloh has said. “Streetwear wasn't on anyone's radar, but the sort of chatter at dinners after shows was like “Fashion needs something new. It's stagnant. What's the new thing going to be?” That was the timeline on which I was crafting my ideas.”

In short order Abloh and West become interns at Fendi, where Abloh meets Michael Burke, CEO of Louis Vuitton, for the first time. Not long after that Abloh launched a boutique called Pyrex Vision, buying up Champion product and deadstock Ralph Lauren Rugby pieces, screen printing over them, and selling them at a huge mark-up. More an art project than a viable brand, he dropped Pyrex to found Off-White in 2013. That brand, informed by the ironic sensibility of quotation marks, zip ties and ‘Caution’ tape, quickly disproved detractors claiming it was a derivative streetwear brand. Year over year, the concepts and designs grew increasingly refined, so that by 2018 the Lyst Index reported Off-White had surpassed Gucci in terms of brand heat. Meanwhile, Abloh is collaborating with the likes of IKEA, Evian, Rimowa, Nike, and Jenny Holzer - just a few topline names in a list of partnerships that goes on and on.

All of this – the studies in architecture, the education alongside Kanye, the fashion houses – feel like rungs on the ladder that finally brought Abloh to March 25, 2018, when he accepted the role of men’s artistic director at Louis Vuitton. It was the kind of historic first that made headlines around the globe, and even better, generated massive buzz among Abloh’s fandom, particularly the enthusiastic cohort of boys and young men who followed Abloh’s every move. Of the appointment, the designer said: "It is an honor for me to accept this position. I find the heritage and creative integrity of the house are key inspirations and will look to reference them both while drawing parallels to modern times".

If Abloh’s work at Off-White was defined by a clever irony, his work at Louis Vuitton felt more earnest and optimistic, both naive and elegant. His debut show in 2018 at Paris’ Palais-Royal Gardens, titled ‘We are the World,’ featured a rainbow ombre runway, a profusion of white suiting, and a cast of models made up partly of his friends. After the show, Abloh would post a photo of himself taking a bow, with a caption designed to galvanize aspiring creatives: “You can do it too.” Followers continue to leave comments on this post years later.

Over the eight collections Abloh produced during his time at Louis Vuitton, he would turn out designs that felt both commercial and innovative, guaranteed to inspire the young cohort he counted among his greatest influences, all underpinned with the immaculate construction and attention to detail one comes to expect from a French luxury house. Always a prolific designer, Abloh had two more collections mostly completed at the time of his death, but the ‘Virgil was here’ show in Miami, presented just two days after his passing, had a particular memorial quality. At the close of that presentation, Abloh’s voice rumbled through the speakers again, saying: “There’s no limit. Life is so short, that you can’t waste even a day subscribing to what someone thinks you can do, versus knowing what you can do.”

In exploring the possible, Abloh made sure to show others their potential, too. A famously open-minded, open-sourced artist, Abloh took pride in sharing “cheat codes” with his followers, tips and tricks he wanted to pass along to the next generation. He did this with talks at Harvard and Columbia, on a website called ‘Free Game’ that provides a masterclass in brand-building, and in a career retrospective exhibit, Virgil Abloh: “Figures of Speech,” which has traveled the world and reappears in the Brooklyn Museum this summer. Then there is his “Post-Modern” Scholarship Fund, designed to present Black students with opportunities in the fashion industry – a fund that has raised $1 million to date. Much of this legacy will continue to be handled by Virgil Abloh Securities, a creative and philanthropic foundation headed by Abloh’s wife Shannon.

Even while his time was running out, Abloh continued to imagine, to innovate, and to lay the groundwork for the creatives who would come afterwards. “The next version of me literally works on my team today. You know, didn’t go to fashion school either, highly ambitious, super creative. And I know maybe 50 of them,” Abloh has said. “They will take my position, they will be the head of Louis Vuitton next, they will start another version of Off-White or a media company or whatever…I know my community is special, and that’s what I’m an advocate for.”

Yes, Virgil was here. And he’s still here - in his designs, in his philanthropic initiatives, and he’s especially here in that next crop of young creatives, in all those young Virgils he helped shape and inspire through his life and work. He was a visionary, a trailblazer, and a lot of other words that can lose currency over time, but maybe most of all Abloh was the spark that lit up the next generation.

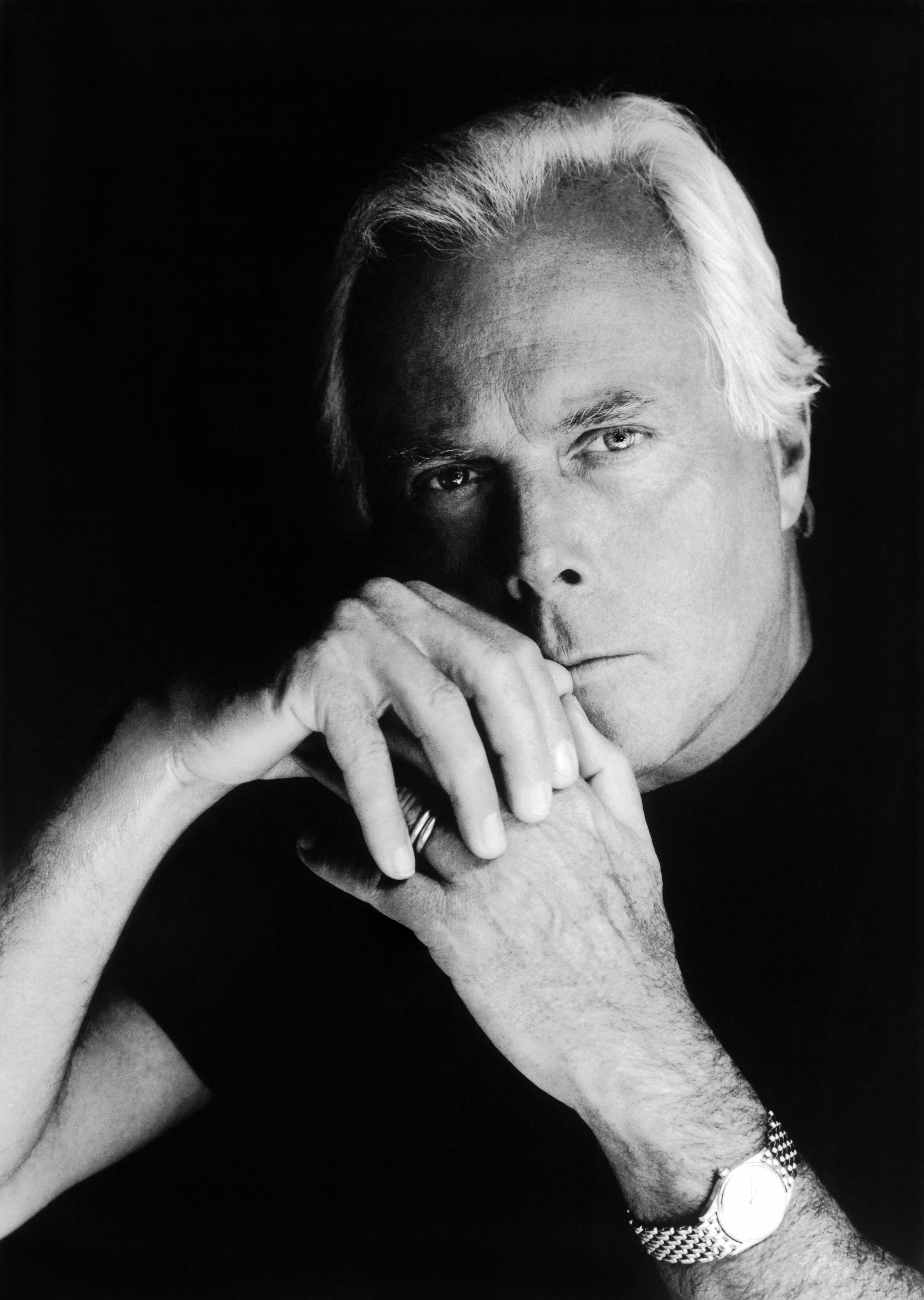

A TOUCH OF THE POET

Valentino’s Pierpaolo Piccioli is making romanticism an achingly personal expression of identity and individuality.

By MAX BERLINGER

Photography MICHAEL BAILEY GATES

Valentino is often thought of in terms of dazzling dresses or flowing couture gowns but lately the Roman brand is taking its designs out of the salons and the ornately designer, grandiose buildings and into the public square. One can’t help but ask – Is Valentino coming down from its ivory tower?

Well, yes and no.

Creative director, Pierpaolo Piccioli has proven a master at injecting a sense of swooning romance into everyday clothes and, conversely, designing ready-to-wear that’s glamorous yet feels as comfortable as a pair of jeans and a T-shirt. His clothes are intentional, celebratory, and lack any pretense of snobbery. It’s this tension that gives the brand a frisson of excitement and grounds it in the realities of modern life. His fashion is a dream, but it’s meant for waking life.

How does Piccioli, who has been in charge of the brand since 2008, and where he worked on the designs jointly with Maria Grazia Chiuri until 2016, resolve these two opposing forces – the romance of fashion and its reality? “I feel that romanticism is an individual approach to life,” he explained. “I don’t think romanticism is about prettiness. For me, romanticism is something that is not objective, just subjective. An individual approach, of course, is about yourself, is personal, is intimate. Sometimes, you cannot explain the reason for your choices – because it’s not objective. But I think that today it is most important to express yourself, to be yourself, to be very close to your identity. That’s the only thing that makes you different.”

Valentino has long been synonymous with an Old World charm – it brings to mind drawing rooms on the Upper East Side or Mayfair populated with socialites and their paramours and its suave founder, with his slicked hair and tan skin. Those days are gone, and Piccioli’s Valentino acknowledges that with clothing that has a relaxed, nonchalant elegance. It’s made not for dinner parties and charity events, but for our busy lives. And yet it’s not devoid of a certain classic glamour – the lush colors, the vivid prints, the dramatic shapes. It shows how one can take the legacy of a brand and move it into contemporary times. Piccioli’s work is a master class of using a brand’s archive to set down a firm foundation for the future.

That sense of playful individuality and expressing oneself has been the animating force of Piccioli’s recent collections, be it in the rarefied worlds of couture, where the everyday uniform is elevated to the highest form of craftsmanship, or his ready-to-wear collections that possess a sense of casual, off-handed elegance. This is a demonstration of the brand’s signature savoir-faire and discernment, yet made for a youthful, cool consumer. A window into how Piccioli is able to bring together the extremes of fashion, the dream of glamor married to the beauty of daily life.

In his work, Piccioli deals mostly with aesthetics – searching for and creating beauty for its own sake. But that doesn’t mean his designs don’t rub up against more metaphysical, philosophical concerns. “I feel that beauty is about grace,” he said. “Grace is not something you can describe, it’s something else – a perception. When I talk with my premières, I never say, ‘I want a centimetre less.’ I say, ‘I would like the dress to move this way, to give this kind of sensation.’ They are so good at their job, they can translate my intention, my idea.”

Interestingly, Valentino has been able to cut through the noise of the social media age with designs that feel achingly personal – the airiness of his couture designs are begging to be touched while the sensual shapes in his ready-to-wear are made to be worn, not just gazed at on a smartphone screen. “To me, luxury is closest to the idea of humanity,” Piccioli explained. That’s the perfect word – humanity. His work feels, at its core, about the wearer, about creating not just a look, but a feeling for the human wearing the clothes. “We are looking for emotional connections much more than any expensive fabric,” he continued. “I don't think that's the big concern. It's something that gives you emotion. And when we talked about exclusivity, it didn’t make sense to me. And neither does inclusivity as just a word. I feel that the image has a power and has a strength. And you use your own language. So fashion is my language.”

The idea of individuality and inclusivity have been an important part of Piccioli’s work in recent years. His runways have been filled not just with models, but characters, interesting personalities who range in ethnicity, age, body type and appearance. This casting choice that’s not only a push for diversity, but an expansion of who Valentino is for – seemingly, these days it's for every type of person.

“As a fashion designer, I want to use my voice to send messages and values that I believe in,” he said, elucidating how a fashion brand can, in its way, move culture. “Through the beauty of the clothes, you can invite people to express themselves however they want to be, wherever they want to be. As a designer, I never want to be what people expect me to be. Wanting to be very faithful to my identity and being different became a value. Now, as the creative director of Valentino, I’m still the same, more or less. I still feel as though every collection is an opportunity to tell something.”

Perhaps that’s what gives Piccioli’s Valentino so much power – his desire to “tell something” as he calls it. His sense of story or narrative imbues the clothing with a drama that’s then brought to life by the diverse assortment of models he uses. These are his characters and the costumes they would wear, this seems to say. And as this story unfolds, beneath the beauty, a stirring message comes through.

This is all by design, of course. “I have political thoughts,” he said. “And I need to tell them, through my language, which is fashion. So, images. If I were a politician, I would be using words. I chose to be a fashion designer, and I want to use my voice to deliver my values. But I think to be relevant is to do it through images because sometimes you can be even more assertive. Not talking, not writing, but through image, through fashion. It’s like a book and a movie – when you read, you have your imagination, you create your own world. With a movie, it’s already there. Fashion can be super-powerful, like a movie – it’s already there.”

These past few years have been trying times for many – the entire world has gone through a vast amount of change. Fashion can sometimes feel superfluous and yet, to dream is to be human. Even in the darkest times, we dream. Piccioli knows his medium – fashion – and his message – to dream. On the Valentino runway, dreams are always present, in dazzling technicolor, in the most luxurious fabrics, made in sweeping, sensual silhouettes. But what we’re left with the most is the stirring emotion. Or as he explained it, “Art is for art's sake and fashion has to do with the body. But what they have in common is that you can create beauty, and you can create curiosity and interest. You can generate emotions that create thoughts.”

WHAT DREAMS MAY COME

Designer Jonthan Anderson and photographer David Sims express a new visual paradigm where freedom is the ultimate experience of life.

By LAURA BOLT

Photography DAVID SIMS

For a man who once said, “I'm not here to please an industry, I'm here to challenge it," Jonathan Anderson has certainly succeeded at defying expectations. Through his own eponymous line and at the helm of Loewe, the Creative Director has found himself part of the constellation of young designers who are reinventing and redefining the industry with fresh takes on form, gender, luxury, and the future.

Anderson, who originally hails from Northern Ireland, has spoken of his work as such: “When I first joined Loewe I went to the Prado, and I walked down this incredibly long corridor of some of the greatest works in history from the Royal collection. There was a Reubens and a Titian, side by side, both of Adam and Eve. They looked identical. But they were by Reubens and Titian. I went through a phase where I didn’t believe that fashion was art, but I do believe that it is a reflection of society, so, therefore it is an art form. It is an interpretation, and it is fine to reinvent. If Reubens can reinvent Titian, then this is fine. For me, that’s the history of the universe there, because ultimately it is about the passing of information.”

Almost two decades older than Anderson, British photographer David Sims is an indelible and undeniable part of the art world, pushing the boundaries of what fashion photography can be. His contributions to publications like The Face and i-D have helped create the aesthetic foundation of British style in the 1990s, and he has also helped push the limits of what brands like Prada, Givenchy, and Valentino could be presented as.

“Most of what inspires what I do is a sort of misremembered event in my life,” he has said of his style. “I’m good at writing myth around myself and I might think of myself as having more emotion at one time, so I tap into some of what the echo of that is.”

In a joint project where Sims photographed Anderson’s work for Loewe in a special edition book, the world has the opportunity to see what happens when two powerful forces collide. The duo found a fortuitous time to collaborate, with the world experiencing unprecedented tumult on a multitude of fronts. Sims’ photographs unapologetically harken back to a time of freedom, release, and hedonism. Inspired by rave culture, Sim’s work with Loewe is insouciant, unexpected, youthful, and ultimately, imbued with a sense of hope and joy that can be hard to come by in both the fashion industry, and in the world at large.

It should perhaps come as no surprise that Sims looked to the rave scene to provide the inspirational underpinnings of his latest work. While fashion and music have always been familiar bedfellows, Sims’ approach to – and participation in – subcultures has become a defining characteristic of his work. Coming to prominence in London during the early 90’s, Sims had a front row seat to the influence of glam, punk, shoegaze, and brit pop – as well as their respective fashions. “It seemed to present something which was more descriptive of a feeling or an emotion or a narrative. The big shift was the subject matter and how that changed the traditional outline of beauty. People want to get back to that,” he has said. “It’s a slightly fascistic thing that was all about presenting power and sex, whereas the grunge image is all about feeling and melancholy. They’re two opposite schools of thought. I think the younger generation want to go back to the latter.”

The music scene provides its own pulse to the work, a sensation that clothes haven’t just been designed, but are being animated and lived in, adding color, shape, and movement set to a syncopated beat. Speaking of his previous work, Sims has said, “We’ve made this journey without ever having left the room. Because the options are limitless, the technique becomes less important. The idea itself is the singular exponent.”

This moment has provided unique ways to interpret a designer’s vision and restructure reality, not just in their creations, but in the ways in which they bring them to fruition. In a time marked by restrictions and constraint, Anderson surprisingly found a sense of freedom in his – and society’s – newfound limitations, reflecting that “limitations can actually be really freeing.” One is reminded of the combination of freedom and constriction experienced during a vivid dream, a dream in which you might be speaking a language you don’t understand, limbs heavy and out of your command, but immersed in a landscape you never thought possible. “Nocturnal is a great word,” Anderson has said when discussing his aesthetic. “This is where we are able to see people when they are free. It’s not a work environment, it’s where you express yourself, where you let go.”

In this dreamscape that Anderson and Sims have created, there is a sense of intimacy and the particular kind of self-expression that feels endemic to a time in one’s life when there is nothing but the future ahead of you. While the idea of luxury generally conjures up images of sumptuous fabrics, rare stones, and detailed craftsmanship, it seems that for Anderson and Sims, it is freedom itself that is the ultimate luxury.

“I find romance in humdrum places,” Sims has said. “I’ve striven to create romantic images, to describe things “romantically.”

To view Sims’ photographs of Anderson’s work is to peer into a world that seems both ecstatic and fleeting, secret, but inviting. It is impossible to deny a certain precocious romance in the unfinished basements, trespassed chain link fences, and crowded bedrooms of the photos. The characters are both inspirational and aspirational, with Sims’ touch presenting them more as memories of friends than models. This approach seems to be an ideal match for Anderson’s design ethos, of which he has said, “I have always approached clothing with this idea that it’s not about genderless clothing and it’s not about sexuality, but it’s just about the individual somehow, almost like you are proposing an individual who has no sort of like place in time,” he explains. “I like building a series of looks because they become different animations of that one character’s attitude. It sort of opens this door where you have to pose something for someone to react against or for yourself to react against. I think for me, it is about the empowerment of a silhouette, which ultimately becomes the intrigue.”

One of the gifts that Anderson and Sims’ collaboration offers the viewer is the chance not to simply admire their art, but to be invited into that world of intrigue, to imbue it with your own experiences, hopes, fears, and secrets. “Life is a spoken mirror and we’re now in a moment where the mirror is incredibly muddied,” Anderson has said. There have been times when the role of art was to hold up that mirror and reflect truth, but these days, it seems more apropos to hold up a mirror in which we can take ourselves through the looking glass into a place that feels altogether new.

“We’re at this very strange moment where it is the beginning of a chapter and I don’t know where we’re going ultimately, which is kind of exciting,” said Anderson. It seems that there has never been a time where our sense of the future seems murkier, but instead of approaching that uncertainty with fear, spending time in the world that Anderson and Sims have created is nudging us to see the potential in that – potential for desire, for change, for beauty, and hopefully, for growth. Ultimately, a world we don’t recognize doesn’t have to be one that doesn’t feel like home.

It is perhaps due to a shared relationship to their work that Sims and Anderson have been able to create a collaboration that feels vivid, of-the-moment, and so satisfyingly able to be imbued with our own desires and memories. “I don’t go out to say that I started something and I own it; I just work with things, Anderson said several years ago. “I think this idea of ownership of design is just ridiculous. I don’t own anything. I make it, I put it out there. That’s it. I move on.” Sims would appear to agree. “You present and re-present your pictures and they gain new significance,” he said. “Just to see it again is a pleasure, but you can’t hold on to it. I let go all the time.” Conspiring, creating, letting go – now there’s a dream we can all share.

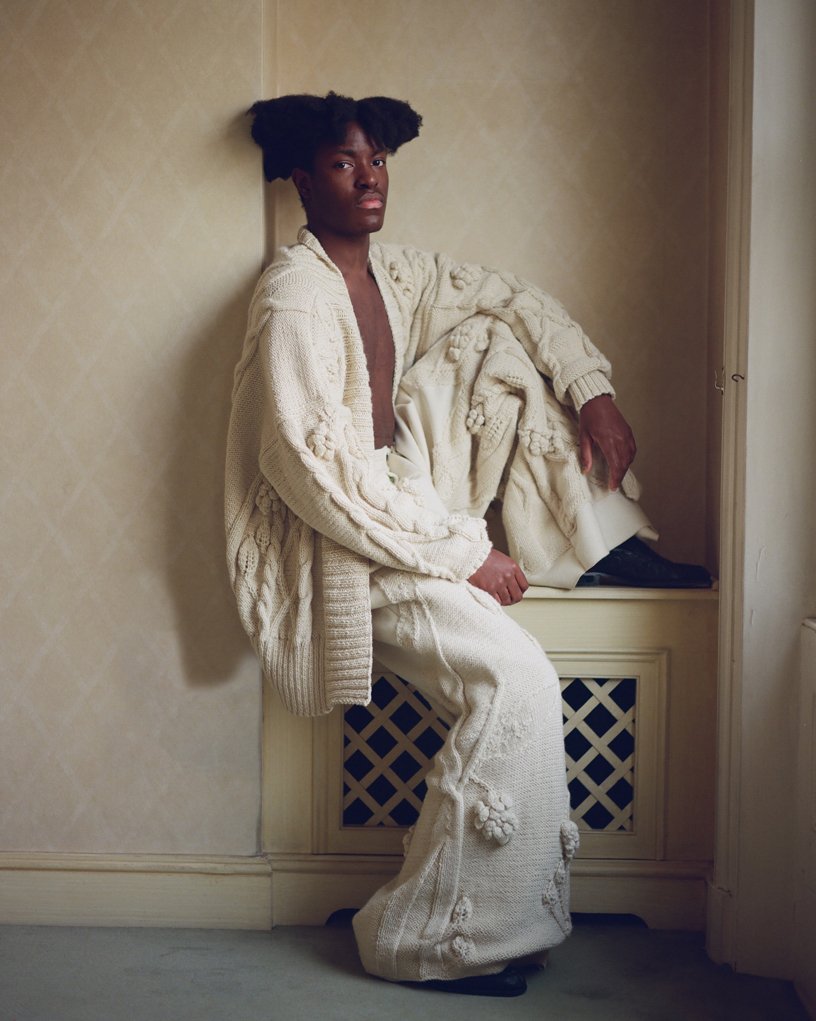

BEAUTIFUL DREAMER

With his eponymous knitwear line, Archie Alled-Martinez reimagines queer history and takes desire to a whole new level.

By JON ROTH

Photography JORGE PEREZ ORTIZ

Sunset, by a secluded lake. A muscled young man in a gauzy top and shimmering pants strips in the wilderness. Someone is watching, but we can’t tell who – we only see his shadow.

Nighttime, on the side of a highway. Two men have pulled their car over onto the shoulder and walk together toward the hood. Headlights blazing, one leans back on the car while the other kneels before him.

Daylight, by the docks. A tanned young man has left his girlfriend in bed to meet a stranger behind the shipping containers. After a stolen moment, he walks away with a handful of cash.

Afternoon at a high school. One boy teases another, and suddenly they are wrestling on the ground, circled by classmates in gym shorts and tank tops, shouting, jeering, egging them on.

These are snapshots from the mind of Archie Alled-Martinez, a knitwear designer with an uncanny ability to zero in on the fraught, erotic tensions that underlie so much of the gay experience. Call them rewritten histories, gay fantasias, wet dreams – in his collections, and his campaign films and photography, the designer couches his clothing in rich historical and cultural contexts, and draws compelling contradictions between the aristocratic, aspirational world of high-end fashion and the secret, sexy, cruisy world of the gay underground. Those contrasts – and of course the clothes themselves: slinky, elegant, cleverly referential – have established Alled-Martinez as a rapidly rising talent.

Which is a bit funny, because at the start Alled-Martinez didn’t even know what knitwear was. Born in Barcelona but having spent much of his young life in England, the designer always knew Central Saint Martins would be the school for him. “I started loving high fashion as a consumer when I was only 14. It’s an age when you start making decisions about what you want to be as an adult,” he has said. “I knew that it had to be London and it had to be Central Saint Martins. I stole my dad’s credit card and I booked a short course there first.” One day as part of these courses, the students were given an introduction to knitwear, and Alled-Martinez says he had to Google what exactly it was.

Once he learned the foundations of the craft, he took to it immediately, relishing the somewhat mechanical work, and the ability to create yard after yard of material, almost by magic. Though he attests he’s not wild about ‘traditional’ knits – "I hate a cable, I hate a jumper; I hate all of that,” – he was quickly able to find his own creative outlet within the form. Partly this was practical: he had to learn the techniques to create the super-fine weaves that are one of his hallmarks. The other part was more of a cultural education, thanks to a book recommendation from one of his professors.

“Fabio [Piras] recommended I read The Beautiful Fall by Alicia Drake. It was all about glamour, the perverse dandy who I’m really attracted to,” Alled-Martinez has said. “That’s really the motor of it. When you have a substantial body of research, of references and imagery, that answers all your questions.”

This in turn led the young designer down a rabbit-hole of research, particularly focused on gay men who captured a zeitgeist, whether in fashion, criticism or nightlife. He’s mentioned Roy Halston, Hal Fischer, and Fabrice Emaer in interviews, but Alled-Martinez’s biggest muse to date has likely been Jacques de Bascher, a patrician Parisian dandy who moved with sinuous grace between the upper echelons of society and the demimonde, along the way capturing the affection of both Karl Lagerfeld and (more briefly) Yves Saint Laurent. In de Bascher the young designer may have seen the same themes and contradictions that inform much of his own work: a swinging ‘70s sensibility, a fine line between luxe and louche, a beauty driven by a fierce underlying sexual magnetism. And, of course, de Bascher drove him to dive deeper into his research of queer culture in that era, a history inextricably bound up with the tragedy of AIDS, and the hedonistic pinnacle that immediately preceded it. “The scenario was super clear: it’s only about 4 years, from ‘78 until ‘82, ’83,” Alled-Martinez has said. “In 1983, Fabrice Emaer died, Le Palace shut down and the whole AIDS epidemic spread. It was such a small amount of time, the peak before the cataclysm.”

As his references grew richer and richer, Alled-Martinez’s designs developed in tandem. In 2018, the year he graduated from Central Saint Martins with an MA in Knitwear, he was also awarded the LVMH Graduate Prize for his collection, a series of garments cunningly rendered to mimic denim, wool, and other tailored materials, but entirely in knits. The award secured the designer a mentorship at Givenchy under Clare Waight Keller, with whom he says he connected instantly. Here he continued to hone his techniques in advance of his first solo presentation in 2020, a fall collection with lots of high-waisted, disco shimmer.

Since then, the Alled-Martinez collections have refined year over year, sometimes playing in the sensual ‘70s space that feels like the brand’s core, other times leaning more into surrealism, or glamor, or sport. In almost every collection there is a carefully conceived narrative that helps drive the designs – narratives that often chart neatly onto pivotal moments in queer history.

Take the designer’s ‘Unsung Heroes’ collection, which featured the names of men like Roy Halston and Jacques de Bascher who had died of AIDS, and the age of their passing. “I didn’t want the names to be gimmicky – maybe people won’t understand what it’s about,” Alled-Martinez has said, while acknowledging, “It’s impactful when you get it.” Impactful, yes, and poignant, and defiant, to bring back the names of gay men who died too young of a disease most of the world ignored at the time. With simple details like this – a name, a number – the designer revives the memory of a generation that is largely lost to us.

Other designs have an outspoken, confrontational edge. One reads “BOTTOMS AND TOPS WE ALL HATE COPS,” a chant that became especially popular during Pride marches in the wake of the murder of George Floyd. Another, reading “HETEROSEXUALS ARE A PROVEN SECURITY RISK,” echoes a protest sign from the National March on Washington for Lesbian & Gay Rights from 1987. Both sentiments can be carried even further back, to the 1969 Stonewall riots, when a police raid of gay bar in Manhattan’s Greenwich Village sparked a confrontation that ignited the modern Pride movement. These reinterpretations and provocations are welcome messages of affirmation for a community that’s often had to speak softly, or in codes, in order to get their point across.

The references are more recent, too. Allied-Martinez’s latest collection explored the low-slung jeans, exposed boxer shorts, and tiny tee shirts of the early aughts, and is inspired by the high school scene of the designer’s youth. He remembers homophobia being pervasive in schools as he was growing up, and wanted to reimagine his youth with those hateful overtones stripped away. “I was wondering what would it be like to have been openly gay during high school,” he said, “and how difficult it was for people in my generation to be themselves growing up.” Even now, queer youth face immense hurdles depending on where they live, so Alled-Martinez’s vision provides a welcome antidote to struggles that continue today.

As his brand grows, Archie Alled-Martinez proves that expertly crafted garments will get you far, but a thoughtful, nuanced point of view will take you even further. It is one thing to collect Instagram followers and dress celebrities based on the viral appeal of a trending shape or color. It is another to craft collections around a story, so that the individual pieces combine into a greater arc.

The goal here is to influence the audience, not just convert them to customers. “If you’re only doing cute clothes and following a trend, it’s only going to last for so long,” the designer has said. “But if you do a collection to create an impact, you might only reach a small audience who will understand the art, but you will get people to think more about a certain subject you find important.”

With designs that immediately spark desire, and stories that chart that desire in new directions, Alled-Martinez is creating with each collection blueprints for a better world, one that acknowledges the hard-fought battles of the past, and points to a way forward. His vision of the future suggests we leave taboos behind, embrace sexual expression, and most of all live freely, as our authentic selves, no matter what the cost. That’s a dream worth fighting for.

PARALLEL UNIVERSE

Korean photographer captures the transformative power of nature for the latest installment of Saint Laurent’s expressive Self project.

By HASSAN AL-SALEH

Photography DAESUNG LEE

An expression of individuality through the work of photographers, artists and filmmakers, Self, curated by Saint Laurent’s creative director Anthony Vaccarello, is an ongoing collaborative project that synthesizes different aspects of the Saint Laurent personality. For its seventh installment, Vaccarello has collaborated with six photographers across six opinion-forming cities including Los Angeles, Paris, London, Seoul and Tokyo. An artistic commentary on society, the artistic exchange is free from pretense and hypocrisy.

In Seoul, Self 07 is viewed through the lens of Korean photographer Daesung Lee. Growing up in a rural village, he was fascinated by nature from an early age and has since become a passionate environmentalist. As an artist, he adopts a conceptual approach in documentary photography, playing between fiction and reality through an enigmatic visualization.

“Spring 2020 was surreal but real. The whole world stopped. No one could easily describe such a feeling in words,” says Lee. “Ironically, nature revived and came back to us once we stopped being indoors. Nature gave us back all the forgotten senses. The sky was so blue, more than ever, birds were singing so loudly out of my apartment window and the leaves of the trees in the streets were greener than ever. It was such a surreal experience. Since then, I no longer see the world in the same way.”

In what can be described as being lost but found, Lee explains, “For the Self project, I attempted to visualize that strange experience during lockdown. An imaginary nature, that you can only see in your inner self, that you can only feel in your own senses. We all lived in our own universe in that time. I hope that you find yourself in these images.”

DAESUNG LEE, MAGNUM PHOTOS GUEST PHOTOGRAPHER FOR SAINT LAURENT BY ANTHONY VACCARELLO.

SEE YOU IN MY DREAMS

Photography MARCO IMPERATORE

Styling EMIL REBEK

Model Mamuor Majeng at Elite Model Management

Hair Stylist Pierpaolo Lai at Julian Watson Agency

Make Up Artist Elena Bettanello at Julian Watson Agency

Casting Director Simone Bart Rocchietti at Simobart Casting

Set Designer Maria Giulia Riva

Set 001 ert chair by studioutte

Photo Assistants Fabio Firenze, Andrea Re

Fashion Assistants Alessandro Ferrari, Flavio Crespi

Executive Producer Justin Gerbino

Retoucher Cristian Buonomo

Production PBJ

CLOSE YOUR EYES

Photography FEDERICA SIMONI

Styling RICCARDO TERZO

Model Mohammed Saliu at Boom

Make Up Artist Simone Gammino at Julian Watson Agency

Set Designer Laura Tocchet

Photo Assistant Luca Soncini

Fashion Assistants Vittoria Santarelli, Aurora Mandelli

Casting WeDoCasting

Post Production Ton sur Ton Retouching

Production Tristan Godefroy

WHEN THE NIGHT FALLS

Photography PAUL PHUNG

Styling KARLMOND TANG

Models Loulou Westlake and Evan Garcia at Chapter Management, Nonso Ojukwu at Elite Model Management, Jinfeng Liu at MiLK Management

Dancers Max Cookward, Oscar Li, Lesya Tyminska, Louisa Fernando

Hair Stylist Moe Mukai

Make Up Artist Chie Fujimoto

Set Designer Sam McDermott

Movement Director Max Cookward

Casting Director Marquee Miller

Photo Assistants Jan-Micheal Stasiuk, Vasily Agrenenko, Jon Riera-Egaña, Ry Francis

Fashion Assistants Megan Harrison, Vedrana Savic

Hair Assistants Nao Sato, Myuji Sato

Make Up Assistant Natsumi Yamamoto

Set Assistants William Green, Ella Fox

A CHARGE TO KEEP

Designer Demna Gvasalia looks to the past and the future with equal measure for the re-birth of couture at the illustrious French maison of Balenciaga.

By MAX BERLINGER

Photography MARK BORTHWICK

There is no type of fashion more personal, more individual, than couture. By its definition, it is a design made to a single body’s specifications, fitted on the individual to help highlight their unique dimensions. At its best, it’s an artform that underscores a person’s sense of self, to show the distinctive aspects of their physical identity, and perhaps something a bit deeper and more nuanced. To reveal who they are, and who they want to be.

It had been 53 years since the luxury brand Balenciaga showed couture, until July of 2021, when the current creative director, Demna Gvasalia, revived the practice. It was the first time since the house’s founder, Cristobal Balenciaga, passed away, that Balenciaga couture made its way down the catwalk. “Over half a century later, I see it as my creative duty to the unique heritage of Mr. Balenciaga to bring couture back to this house,” Gvasalia explained. “It is the very foundation of this century-old maison.”

It was worth the wait. Gvasalia bridged the gap between the collections shown in 1968 and now. He took couture - a type of making clothes that is heavily influenced by the past - and brought it boldly into the present. At the same time, he charted a path for its future, forging a new sense of identity and understanding. As Gvasalia describes it, “a very personal vision of the essence of fashion.”

When Monsieur Balenciaga was designing for his house, ballgowns and opera coats were the traditional fare of the couture. He was known for his exacting eye and ability to create new, exciting, and surprising silhouettes from tulle and chiffon. It’s why Christian Dior once said of Balenciaga, “He is the master of us all.” It’s the reason why the brand continues to enchant and seduce us all these years later.

Gvasalia has a similarly brilliant mind, and one attuned to the ways that fashion is quickly evolving, trying to keep up with the never-ending speed of the Internet. He has understood, for instance, that hoodies and sneakers are the most culturally relevant clothing for young people, and has built a large part of his work at Balenciaga around these pieces. More than that, though, he’s created a certain mood for the brand, one that’s based on new, exciting, and surprising silhouettes – the same thing Balenciaga built his reputation on – but this time it’s parkas with bold shoulders, soupy, flowing track pants, and casual sneakers of enormous size. Over that, he’s imparted a sly irony and a foreboding sense of angst. It perfectly reflects the strange, off-kilter times in which we find ourselves. “It completes my multi-layered vision for Balenciaga the brand which ranges all the way up from streetwear into conceptual fashion and wardrobe and ultimately into one-of-a-kind, made-to-measure couture pieces.”

His debut couture collection carried that thread on from stark, meticulous tailoring that reimagined suiting not as sleek and body skimming but hulking and imposing to the dresses that were shapely and voluminous, beaded and embellished, a call back to the days of Balenciaga’s work. Many of the designs were directly referencing pieces from the archive, Gvasalia said.

“We cannot only look to the future,” he said. “We have to look into the past to see where we’re going.” He continued, “Clothes have a psychological impact on me. I realized they make me happy – and I realized that’s the purpose of fashion. It’s not about the frenzy and buzz – and the white noise, I call it, of the digital mayhem we’re living through. The essence of it is my passion and the tools. I realized that couture is the best way to manifest it. And this is what really turns me on.”

In other words, Gvasalia is making clothing that’s not about posting on social media for likes though plenty of people do that, but to help you align with your truer self – for you to build your identity from the outside in. For the couture collection, that meant everything from oversized suits to sportswear to enormous party dresses, but more than that, it meant pursuing beauty at its highest form. “Couture is above trends, fashion and industrial dressmaking,” he said. “It is a timeless and pure expression of craft and architecture of silhouette that gives a wearer the strongest notion of elegance and sophistication.”

At its core, couture is an artform that is about craftsmanship and integrity, and Gvasalia was able to infuse those ideas into even the most common of garments. T-shirts, for example, were made from a padded silk and, Gvasalia said, required multiple fittings. There were even blue jeans, but with the denim made in Japan and lined in silk. “Couture is the highest level of garment construction, that is not only relevant in today’s mass productive industry, but even absolutely necessary for the survival and further evolution of modern fashion.”

Some collections are beautiful and wearable, but this did something more. It spoke to the way clothing reflects the zeitgeist, revealing something about who we are right now. It spoke to our post-pandemic era, where we are all looking for clothing that is hopeful, good for the planet, and expresses something about ourselves.

Gvasalia laid-out his plans for the couture, simply and succinctly, “It’s a trench coat. It’s a tailored suit. I will even have a couture T-shirt. I need to extend it. For couture to be modern, it has to be a wardrobe. We cannot get locked into the ballroom.”

Well, Gvasalia has certainly freed us from the confines of the ballroom. His couture collection is one made for the streets, made for real life, for real people. But that doesn’t ignore the artistry and skill that’s demanded of the couture artform, a history that is passed down through the hands of artisans who create these garments that dare to dream about beauty and life in the most whimsical and wonderful ways. It helps tell our history in jackets and pants.

“For me, it was the beginning of a new era. I’m not talking about Balenciaga, but about myself as a designer. It was a moment I have been looking forward to and been quite afraid of.”

And then he added, “I feel at peace.”

A WONDERFUL WORLD

Gucci’s series of endless births over the last century embody and embrace an interdisciplinary understanding of gender and identity where everything connects to anything.

By MAX BERLINGER

At 100 years old, Gucci is not just surviving amid a time of unprecedented change, but thriving. The internet, social media, the aftermath of the pandemic, and widespread sociopolitical growing pains are just some of the sweeping events that have upended the fashion business over the past two years. And yet Gucci has chugged along, creating beauty and desire for generation after generation. As the brand reaches this important milestone, its powers to intoxicate consumers may well be at their peak.

Alessandro Michele, Gucci’s exuberant creative director since 2015, has redefined the look of the Italian label, injecting it with a maximalist eccentricity. Today, the brand is known for its nerdy-chic, gender-fluid, and poetic look, full of romantic blouses, logo-strewn sportswear, and sexy, 1970s inspired tailoring. His collections have become sprawling sartorial universes, that offer goodies for any style archetype. Granny chic, sylphlike tailoring, flashy sportswear, restrained elegance – it’s all there for the picking. It’s not dogmatic, but mutable, in line with the way that Gen Z has embraced a fluid approach to fashion, gender, and life. Michele’s Gucci unapologetically embraces the notion that identity is not a static construct - it is dynamic and contextual. It says that there is a Gucci for every type of person in the world, that there is a place for everyone in its tribe.

As American journalist Frank Bruni succinctly puts it, “Michele’s Gucci is engaged in a consistently spirited and occasionally profound conversation with the zeitgeist, drawing from it, adding to it and revolutionizing fashion in the process. Young consumers plant their flags and sculpt their images on social media, so Gucci, under Michele, does too. They expand and even explode the old parameters around gender, sexual identity, race and nationality, and Michele takes that journey with them, even leads them on it, giving them a uniform for it, a visual vocabulary with which to express it. The emotional genius of what he has done is to affirm their searching.”

Gucci was originally founded in Florence as a luggage shop, by the enterprising Guccio Gucci. His store sold imported travel bags but, crucially, had its own workshop onsite that made custom luggage. Eventually that business became the core of the Gucci empire. Under Guccio’s son Aldo, the brand’s reach expanded, becoming an empire known across the world. A string of hit products – the Bamboo bag, its signature loafers, the “Jackie” bag and its Flora scarf – made Gucci a go-to for the fashion cognoscenti, and provided a design foundation that remains central to the brand. These items are reinterpreted again and again and remain part of the current roster of covetable products. The brand opened stores internationally and became part of the firmament of luxury brands.

During the 1980s, contentious family drama played out behind-the-scenes as the brand continued to flourish, but it was during the 1990s that the brand’s superstar status was cemented by the designer Tom Ford. Ford, a stealthy American, brought an unabashed, swaggering sensuality to the label. Later, the Italian designer Frida Giannini added a more feminine, romantic touch, and after she left, Michele, who worked under her, was promoted. He put an immediate maximalist stamp on the brand, blending Ford’s sensuality and Giannini’s romance, but adding an over-the-top, eccentric sense of Italian rococo. Today, the brand is for those who value individuality, and embrace fashion as a means of expressing their strangest, most outlandish desires.

“Going through the hour when everything originated is a great responsibility for me, and a joyful privilege,” Michele said in his typically florid style. “It means being able to open the locks of history and linger over the edge of the beginning. It means soaking in that natal source to relive the dawn and the coming into view.”

“The whole spirit of it was a complete revolution, a deep change.” Adrian Joffe, the president of Comme des Garçons and the store Dover Street Market, said of Michele’s revolution. “Alessandro tells a story.”

Michele’s story is often inspired by Italian culture and history, like a Renaissance painting and dreamy poetry. But in his work you can see a sponge-like brain that pulls from everything – pop culture, theatre, film, music, events from the recent past or from eons ago. Michele is known in the fashion world as a sort of philosopher of clothing, someone who ruminates deeply on what we wear and what it all means. “In Italian, we can say that beauty is something that you create – that you create the illusion of your life,” he said. “It is to believe in something that doesn’t exist, like a magician, or a wizard. The purpose of fashion is to give an illusion. I think that everybody can create their masterpiece, if you build your life how you want it. Just to create that illusion of your life – this is beautiful.”

Under his watch, the brand has exploded – it’s seen in magazines, on red carpets, and, perhaps most importantly, on regular people wishing to communicate some secret part of themselves to the world. It has experienced its own Renaissance of sorts, one that perfectly dovetails with the brand's big anniversary. “I wouldn’t like to sentimentalize a biography though,” Michele said. “Gucci’s long history can’t be contained within a single inaugural act. As any other existence, its destiny is marked by a long series of endless births and constant regenerations. In this persistent movement, life challenges the mystery of death. In this hunger for birth, we have learnt how to dwell the time.”

He added, “I felt like celebrating 100 years of Gucci, which is not only fashion, it’s the essence of fashion, it’s life and its great strength is being so popular. Gucci is a film, a song, a world, a character from a movie, a pop star.”

That’s not typical talk from a designer, but it does reveal a bit about why Michele’s work is so powerful, and so popular. Beyond the glitz and glamour, there’s a certain elegiac ache, a nostalgia, and a little bit of sadness. While most designers traffic in sex and glamour, there’s something so potent about garments that, together, conjure a wide spectrum of human emotions, as Michele does. Michele’s work isn’t two-dimensional, but represents the complexities and contradictions of life. Perhaps the most impressive feat that Michele executes is to stuff his collections with many references and inspirations, but never allow the looks to be weighed down under them. “In my work, I caress the roots of the past to create unexpected inflorescences, carving the matter through grafting and pruning,” he explains. “I appeal to such ability to reinhabit what has already been given. And to the blending, the transitions, the fractures, the concatenations. To escape the reactionary cages of purity, I pursue a poetics of the illegitimate.”

That takes a sharp mind, a light touch, and a bit of dazzling genius. These are things Michele has proven to be collection after collection. “An alchemical factory of contaminations where everything connects to anything,” as Michele describes it in his own words.

Even 100 years on, Michele still sees the brand as “an infant that is constantly reborn and recreated. It’s incredible how Gucci has gone through multiple lives and continues to be so popular.” Gucci’s “natural rebirth”, according to Michele, is “a sign that fashion is not finished and will never finish - independently of any fashion week. Fashion is a representation of life and can self manage.”

But as Michele reminds us, “The promise of a never-ending birth is only renewed through an evolving capacity.”

DEEP WITHIN

Imprinting multiple identities onto Louis Vuitton’s iconic creation pays tribute to its founder’s visionary soul.

By RADHINA COUTINHO

If one ever had to choose a fitting metaphor for the mind of a creative genius, a trunk could serve as a strong contender. A repository of your most personal items, indispensable necessities for a journey – whether physical, emotional or spiritual – selected to accompany you as you voyage through every new chapter in your life.

For Louis Vuitton it’s perhaps fitting that his most emblematic creation – the LV trunk– was chosen by the eponymous house he founded in 1854 as the vehicle to celebrate his visionary spirit during his bicentennial year.

The LV trunk was reimagined hundreds of times by its original creator – somehow managing to be both iconic yet undisputedly individual. Louis was called upon to create carrying cases to encase items that were true extensions of their owners’ selves – from famed conductor Pierre Sechiari’s precious Stradivarius to portable libraries designed for lengthy Transatlantic journeys, providing travelers with both intellectual sustenance and companionship on the long days on the waves. His beautiful creations served to both conceal and protect their owners’ most personal possessions, while simultaneously signaling to the world that they were precious enough to warrant the creation of a made-to-measure carry case.

Each owner imprinted his or her own identity on their trunk – and therein lay the seed of 200th year celebrations, marking the birth of the house’s visionary founder in 1821.

With Louis 200, the venerated French fashion house asked 200 creative minds to reimagine the form of an LV trunk in a manner that pays homage to Louis Vuitton’s synergetic spirit. The creative endeavor also salutes the many, truly revolutionary collaborations that have marked the tenure of a brand that today is synonymous with true luxury – collaborations with proven genius as well as exploratory endeavors with emerging talent.

“Imagine having a conversation with not just one visionary, but 200,” said Faye McLeod, Louis Vuitton’s visual image director. “There’s an exceptional energy that emanates from them – this constant flow of creativity. People will really sense the feeling of celebration,” he added.

The collaborative call out has been effusively embraced by individuals who have made their mark on a myriad of artistic avenues – everyone from Susan Miller, astrologer to Hollywood’s biggest stars, to yo-yo world champion Gentry Stein have attempted to distill their interpretation of originality into the form of the iconic LV trunk. The resulting 200 creations perhaps best reveal that magical quality of a traveler’s trunk – a relatively non-descript item that can hold within it all manner of unimaginable beauty, often only hinted at by its individual form.

This quality of simultaneously concealing and revealing is perhaps one of the reasons why Syrian-born Swedish conceptual artist Jwan Yosef was invited to lend his unique perspective to the project. It’s a subject that he revisits regularly in his work. Representation features strongly in his repertoire – one element standing in place of another – whether this be old family photographs or powerful cult images that contain the emotion of collective memory.

Speaking about his contribution “A Study for Touch” to the Louis 200 celebration of creativity, Yosef says it was all about “revealing what was not meant to be seen, almost undressing an object”. With the trunk itself he chose to play with the canvas, painting large portraits using sweeping bold brushstrokes, stretching them up and then unravelling them before draping them onto a trunk shape, in a way revealing the rawness of the object that is not meant to be seen. “It’s a play of choosing to cover, or to dress, and in this way I think it became undressed?” says Yosef.

This play of hidden, often mystical influences on the creative spirit is what revered astrologer Miller, too, chose to focus when creating her unusual LV trunk. The interior of her trunk features a to-scale representation of the solar system as it looked at the time Louis Vuitton was born on August 4th 1821, in the early hours of the morning.

According to Miller, Vuitton was destined for greatness from birth, with a brilliant chart that revealed enormous creativity, a quest for excellence in quality and detail, and the ability to encourage greatness in others. Her unusual interpretation of Vuitton’s well-aligned stars serves to underscore the mercurial mix of talent, luck, timing and foresight that tend to mark the life of any great maverick. Like the artistic drive itself, the opportunity for interpretation of the brief has proved truly limitless, stepping back into the trunk’s heritage as well as daring to imagine its bold future.

Take LA-based interiors and entertainment designer Willo Perron’s response. "I wanted to take the form of this object that was created 200 years ago and transform it into something contemporary and futuristic,” says Perron. “Will the trunk of the future walk itself to its destination? Will it open up and unpack and then re-pack itself? When it’s not being used, can it live as a beautiful object that sits in your home? How do you take such an iconic object and transform it for the future?"

Perron’s answer involved the creation of a solid aluminum box – a very simple, polished object from the outside that opens to reveal a dramatic robotic-like interior filled with mobile parts that almost “dance” together, in Perron’s own words – a nod to his background in the performance arts, visually almost resembling the rigging of a concert stage.

If Perron’s creation imagines the future of the trunk, others such as Lebanese composer Zad Moultaka, delved deep into their own pasts for inspiration. His “wonder trunk” recalls the innocent magic of a simple fairground staple.

“Fifty years ago, in my grandmother’s village, I see myself running again with other children, 25 piastres in my hand behind an old man dragging a ‘wonder box’ on a roulette wheel. 25 piastres for a ticket gave us the right to look through the two holes inside the trunk, for a few minutes. All kinds of images scrolled slowly and carried us to a magical journey that emerged in front of our amazed eyes. What is more challenging and poetic than to recall this memory to celebrate the two hundred years of Louis Vuitton?” says Moultaka.

Moultaka went back to Vuitton’s portrait to complete the concept. “Using Vuitton’s eyes as the main element to imagine the outside of the trunk was obvious,” he continues. “The motif of Vuitton’s eyes is duplicated and repeated in a particular rhythm to create a feeling of dreamlike dizziness and hallucination.”

Moultaka’s trunk features two holes – representing the pupils, meant to “sharpen our curiosity as ‘voyeurs’ and induce us to look and discover what is happening inside the trunk. Poetic landscapes scroll slowly in front of our eyes, they are made from fabrics, clothing and other traveler’s belongings filmed in close‐ups, becoming sea, dunes and mysterious mountains. When the trunk opens a little melody is played like a music box conducting the magic of this intimate journey,” concludes Moultaka.

This amalgamation of past, present and future – intertwining dreams and hopes with a philanthropic spirit for a better tomorrow – is the common thread that runs through the 200-year celebration; not just finding its voice in the charitable element that lies at the heart of the project that will enable young individuals from across the globe to discover the arts, but also in the reimagination of the trunks themselves.

French sculptural artist Amande Haeghen’s LV trunk personifies this idea of time, layering, imprinting. Haeghen built up layers – each bearing the imprint of the previous one – by mixing materials such as earth, glass, metal, plaster, and pieces of wood. The structure so created is reminiscent of that of a trunk, “crystallizing this notion of time and imprint of the past but also on the future,” she says.

"200 years remind us that against time, no one can do anything. The realization of this passing time, sedimentation, a process in which particles of any matter gradually stop moving and come together in layers. These layers that are created, year after year, to form a universal memory, that of the earth and our imprint. So many thicknesses, like the pages of a book telling us the story, our story. It is in this spirit of accumulating experiences and exchanges that I deeply believe in exploring this idea of sedimentation of memory and mimesis,” says Haeghen.

The idea of imprinting of identities is something that has run through Louis Vuitton’s illustrious heritage – finding its voice in the many avant-garde and unexpected collaborations that have punctuated the house’s history through the ages, and marking its ability to reinvent and transmute itself to appeal to an ever-wider audience – one that stretches across borders, stylistic persuasions and senses of selves.

From Marc Jacobs and Sprouse’s landmark reinvention of the sacrosanct LV logo, imprinting Sprouse’s own trademark acid pink graffiti scrawl on its iconic form, to the many iterations of the LV trunk that have embodied their creators’ artistic drives, this synergistic exercise has once again underscored how the notion of creativity and identity can be unpacked in many different ways.

Somehow it feels like Louis would have approved.

DANCING WITH A STRANGER

Photography JAVIER CASTÁN

Styling GABRIELLA NORBERG

Fashion LOUIS VUITTON

Model Momo Ndiaye at The Claw Models

Dancers Alpha Bcz, Aaron Comino, Ignacio Gimenez, Manuel Monró

Hair and Make Up Artist Paca Navarro at Kasteel Management

Casting Director David Chen

Movement Director Ester Guntín

Set Designers Indra Zabala, Adrià Escribano

Photo Assistant Pablo Rincón

Fashion Assistant Sara Biriukov

Set Assistant Joan Bustos

POETRY OF LIFE

French designer Simon Porte Jacquemus tells a timeless story of pastoral beauty and simple pleasures, one image at a time.

By JON ROTH

Photography SIMON PORTE JACQUEMUS

The first time you came in contact with Jacquemus, it almost certainly happened on Instagram. Maybe you scrolled past a sun-struck country field, or a bowl of citrus, or a handsome, smiling man looking directly at the camera. Maybe you even saw a garment or accessory from the French fashion house – a very tiny bag, for example, or a wildly oversized hat. You may not have made the connection between the field of wheat or the bowl of lemons and the growing brand behind it, but the image likely spoke to you all the same, conjuring happy memories of warm places, and so in that first encounter, Simon Porte Jacquemus had already achieved his goal: to make you smile.

There is a formula of sorts to Instagram success, and it’s easy enough to learn: bright pops of color, beautiful people and beautiful places, a hint (but just a hint) of sex, simple, straightforward images, and just enough humor so everyone knows you’re not taking this too seriously. Simple enough for an individual to recreate, and yet few fashion brands can pull it off without seeming stiff, or corporate, or try-hard. Jacquemus, still a relatively young brand, only makes it seem effortless thanks to the steady vision of 31-year-old founder Simon Porte Jacquemus, a man with a singular talent for image-making.

We are all image-makers, even if we don’t paint or design. Everyone is caught up in the daily creation of their own image – the persona that they present to the world. A person’s identity and their image aren’t quite identical, but they are closely bound. The first is the essence of the self, the second is the part of themselves they choose to share – and increasingly, what we share of ourselves, we share on social media. Whether it is true or not, Jacquemus the man suggests his image and his identity are the same. He seems to have no filters, or pretenses, or affectations. He unapologetically savors simple pleasures. And this approach has made him a fashion favorite.

To follow Jacquemus’ story in new clippings over the years is to see his follower count climb exponentially. At press time, he has 3.8 million followers on Instagram. Reporters rarely fail to mention those numbers, because so much of the brand’s appeal comes through on the account. Sure, detractors could claim that Jacquemus is only image, without the substance to back it up, but then fashion is all about selling us on an image. And Jacquemus sells extremely well – the designer estimated his business at around 25 million euros in 2019.

What is it about the Jacquemus image, specifically, that resonates so strongly? It’s that warm, sunny feeling. The artlessness, mixed with sexiness, mixed with a certain viral je ne sais quoi the designer seems born with, but has likely honed over years as an Internet native. Above all, the Jacquemus vision is joyful. It doesn’t ask much of its audience, except that they take pleasure in what they are seeing - and hopefully, eventually, wearing - and that alone is at odds with the fashion world at large, where the current trends toward the dark, the edgy, the intellectually difficult. Where many other brands seem to offer a puzzle, Jacquemus presents a dream you can take part in.