BEAUTIFUL DREAMER

With his eponymous knitwear line, Archie Alled-Martinez reimagines queer history and takes desire to a whole new level.

By JON ROTH

Photography JORGE PEREZ ORTIZ

Sunset, by a secluded lake. A muscled young man in a gauzy top and shimmering pants strips in the wilderness. Someone is watching, but we can’t tell who – we only see his shadow.

Nighttime, on the side of a highway. Two men have pulled their car over onto the shoulder and walk together toward the hood. Headlights blazing, one leans back on the car while the other kneels before him.

Daylight, by the docks. A tanned young man has left his girlfriend in bed to meet a stranger behind the shipping containers. After a stolen moment, he walks away with a handful of cash.

Afternoon at a high school. One boy teases another, and suddenly they are wrestling on the ground, circled by classmates in gym shorts and tank tops, shouting, jeering, egging them on.

These are snapshots from the mind of Archie Alled-Martinez, a knitwear designer with an uncanny ability to zero in on the fraught, erotic tensions that underlie so much of the gay experience. Call them rewritten histories, gay fantasias, wet dreams – in his collections, and his campaign films and photography, the designer couches his clothing in rich historical and cultural contexts, and draws compelling contradictions between the aristocratic, aspirational world of high-end fashion and the secret, sexy, cruisy world of the gay underground. Those contrasts – and of course the clothes themselves: slinky, elegant, cleverly referential – have established Alled-Martinez as a rapidly rising talent.

Which is a bit funny, because at the start Alled-Martinez didn’t even know what knitwear was. Born in Barcelona but having spent much of his young life in England, the designer always knew Central Saint Martins would be the school for him. “I started loving high fashion as a consumer when I was only 14. It’s an age when you start making decisions about what you want to be as an adult,” he has said. “I knew that it had to be London and it had to be Central Saint Martins. I stole my dad’s credit card and I booked a short course there first.” One day as part of these courses, the students were given an introduction to knitwear, and Alled-Martinez says he had to Google what exactly it was.

Once he learned the foundations of the craft, he took to it immediately, relishing the somewhat mechanical work, and the ability to create yard after yard of material, almost by magic. Though he attests he’s not wild about ‘traditional’ knits – "I hate a cable, I hate a jumper; I hate all of that,” – he was quickly able to find his own creative outlet within the form. Partly this was practical: he had to learn the techniques to create the super-fine weaves that are one of his hallmarks. The other part was more of a cultural education, thanks to a book recommendation from one of his professors.

“Fabio [Piras] recommended I read The Beautiful Fall by Alicia Drake. It was all about glamour, the perverse dandy who I’m really attracted to,” Alled-Martinez has said. “That’s really the motor of it. When you have a substantial body of research, of references and imagery, that answers all your questions.”

This in turn led the young designer down a rabbit-hole of research, particularly focused on gay men who captured a zeitgeist, whether in fashion, criticism or nightlife. He’s mentioned Roy Halston, Hal Fischer, and Fabrice Emaer in interviews, but Alled-Martinez’s biggest muse to date has likely been Jacques de Bascher, a patrician Parisian dandy who moved with sinuous grace between the upper echelons of society and the demimonde, along the way capturing the affection of both Karl Lagerfeld and (more briefly) Yves Saint Laurent. In de Bascher the young designer may have seen the same themes and contradictions that inform much of his own work: a swinging ‘70s sensibility, a fine line between luxe and louche, a beauty driven by a fierce underlying sexual magnetism. And, of course, de Bascher drove him to dive deeper into his research of queer culture in that era, a history inextricably bound up with the tragedy of AIDS, and the hedonistic pinnacle that immediately preceded it. “The scenario was super clear: it’s only about 4 years, from ‘78 until ‘82, ’83,” Alled-Martinez has said. “In 1983, Fabrice Emaer died, Le Palace shut down and the whole AIDS epidemic spread. It was such a small amount of time, the peak before the cataclysm.”

As his references grew richer and richer, Alled-Martinez’s designs developed in tandem. In 2018, the year he graduated from Central Saint Martins with an MA in Knitwear, he was also awarded the LVMH Graduate Prize for his collection, a series of garments cunningly rendered to mimic denim, wool, and other tailored materials, but entirely in knits. The award secured the designer a mentorship at Givenchy under Clare Waight Keller, with whom he says he connected instantly. Here he continued to hone his techniques in advance of his first solo presentation in 2020, a fall collection with lots of high-waisted, disco shimmer.

Since then, the Alled-Martinez collections have refined year over year, sometimes playing in the sensual ‘70s space that feels like the brand’s core, other times leaning more into surrealism, or glamor, or sport. In almost every collection there is a carefully conceived narrative that helps drive the designs – narratives that often chart neatly onto pivotal moments in queer history.

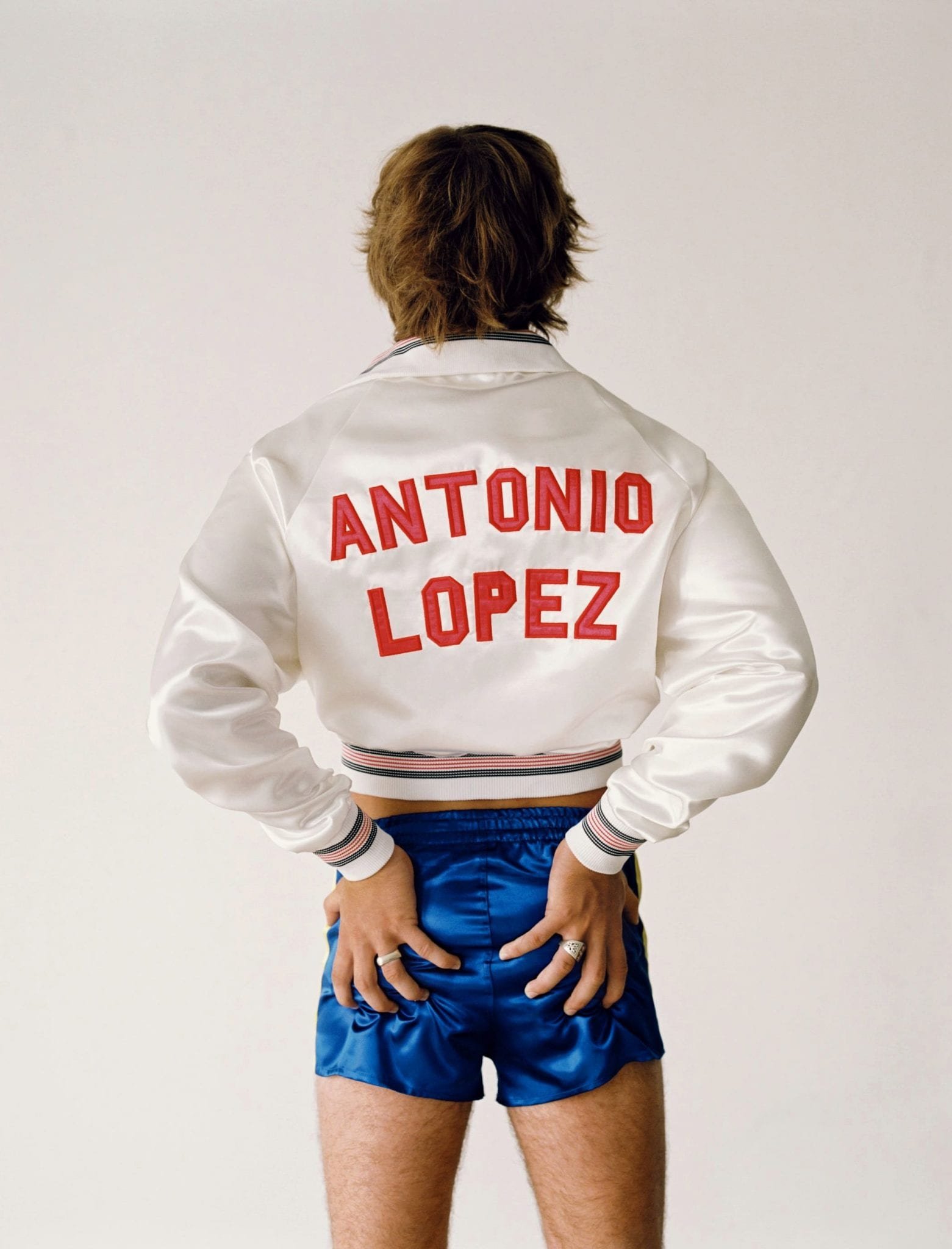

Take the designer’s ‘Unsung Heroes’ collection, which featured the names of men like Roy Halston and Jacques de Bascher who had died of AIDS, and the age of their passing. “I didn’t want the names to be gimmicky – maybe people won’t understand what it’s about,” Alled-Martinez has said, while acknowledging, “It’s impactful when you get it.” Impactful, yes, and poignant, and defiant, to bring back the names of gay men who died too young of a disease most of the world ignored at the time. With simple details like this – a name, a number – the designer revives the memory of a generation that is largely lost to us.

Other designs have an outspoken, confrontational edge. One reads “BOTTOMS AND TOPS WE ALL HATE COPS,” a chant that became especially popular during Pride marches in the wake of the murder of George Floyd. Another, reading “HETEROSEXUALS ARE A PROVEN SECURITY RISK,” echoes a protest sign from the National March on Washington for Lesbian & Gay Rights from 1987. Both sentiments can be carried even further back, to the 1969 Stonewall riots, when a police raid of gay bar in Manhattan’s Greenwich Village sparked a confrontation that ignited the modern Pride movement. These reinterpretations and provocations are welcome messages of affirmation for a community that’s often had to speak softly, or in codes, in order to get their point across.

The references are more recent, too. Allied-Martinez’s latest collection explored the low-slung jeans, exposed boxer shorts, and tiny tee shirts of the early aughts, and is inspired by the high school scene of the designer’s youth. He remembers homophobia being pervasive in schools as he was growing up, and wanted to reimagine his youth with those hateful overtones stripped away. “I was wondering what would it be like to have been openly gay during high school,” he said, “and how difficult it was for people in my generation to be themselves growing up.” Even now, queer youth face immense hurdles depending on where they live, so Alled-Martinez’s vision provides a welcome antidote to struggles that continue today.

As his brand grows, Archie Alled-Martinez proves that expertly crafted garments will get you far, but a thoughtful, nuanced point of view will take you even further. It is one thing to collect Instagram followers and dress celebrities based on the viral appeal of a trending shape or color. It is another to craft collections around a story, so that the individual pieces combine into a greater arc.

The goal here is to influence the audience, not just convert them to customers. “If you’re only doing cute clothes and following a trend, it’s only going to last for so long,” the designer has said. “But if you do a collection to create an impact, you might only reach a small audience who will understand the art, but you will get people to think more about a certain subject you find important.”

With designs that immediately spark desire, and stories that chart that desire in new directions, Alled-Martinez is creating with each collection blueprints for a better world, one that acknowledges the hard-fought battles of the past, and points to a way forward. His vision of the future suggests we leave taboos behind, embrace sexual expression, and most of all live freely, as our authentic selves, no matter what the cost. That’s a dream worth fighting for.